Küps, Karas, Kvevris, Dolias, Pithos, Tinajas, Talhas de barro und Amphoren

Udo Hirsch, Güzelyurt/Türkei 2016

(publiziert in: keiko&maika. 2016, Voyage en Amphore, WOINO, Villfranche sur Mer, France)

Vorgeschichte

Geknüpfte Tragnetze, Taschen und Eimer aus Holz und Tierhäuten, mit Gips ausgestrichene geflochtene Körbe, Kürbisschalen, kleine und große Gefäße aus Holz und aus Stein und andere natürliche Behälter wurden schon lange vor dem Seßhaftwerden von Jäger -und Sammlergruppen verwendet. An Orten mit besonders reichen Nahrungsressourcen konnte man sich länger aufhalten, oder auch immer wieder zurückkehren. Hier fanden Archäologen in den Fels geschlagene Steingefäße und sogar aus Stein geschlagene große Tröge.

Einige dieser noch nicht seßhaften Jäger- und Erntegruppen bauten gewaltige Tempelanlagen und feierten üppige Feste. Eine solche Tempelanlage ist Göbekle Tepe bei Urfa im Südosten der Türkei. Nach nur kurzer Zeit des Gebrauchs wurde die Anlage mit Steinschutt und einer gewaltigen Menge Tierknochen aufgefüllt. In direkter Nachbarschaft der Anlage fand man große Steintröge und in den Fels geschlagene Steinwannen mit einem Fassungsvermögen von zweitausend Liter und mehr. In solchen Steinbassins wurden geringe Rückstände von Calcium Oxalat gefunden, das beim Zerreiben und Fermentieren von Getreide entsteht und auf die Produktion von Malz und das Brauen von Bier für die Tempelfeste hinweist. 1

1. Ausgrabung Göbekle Tepe. Felsplatte mit ausgeschlagenem großem Felsdepot und kleinen Vertiefungen. Hier wurden möglicherweise Gerstenkörner fermentiert und Bier gebraut.

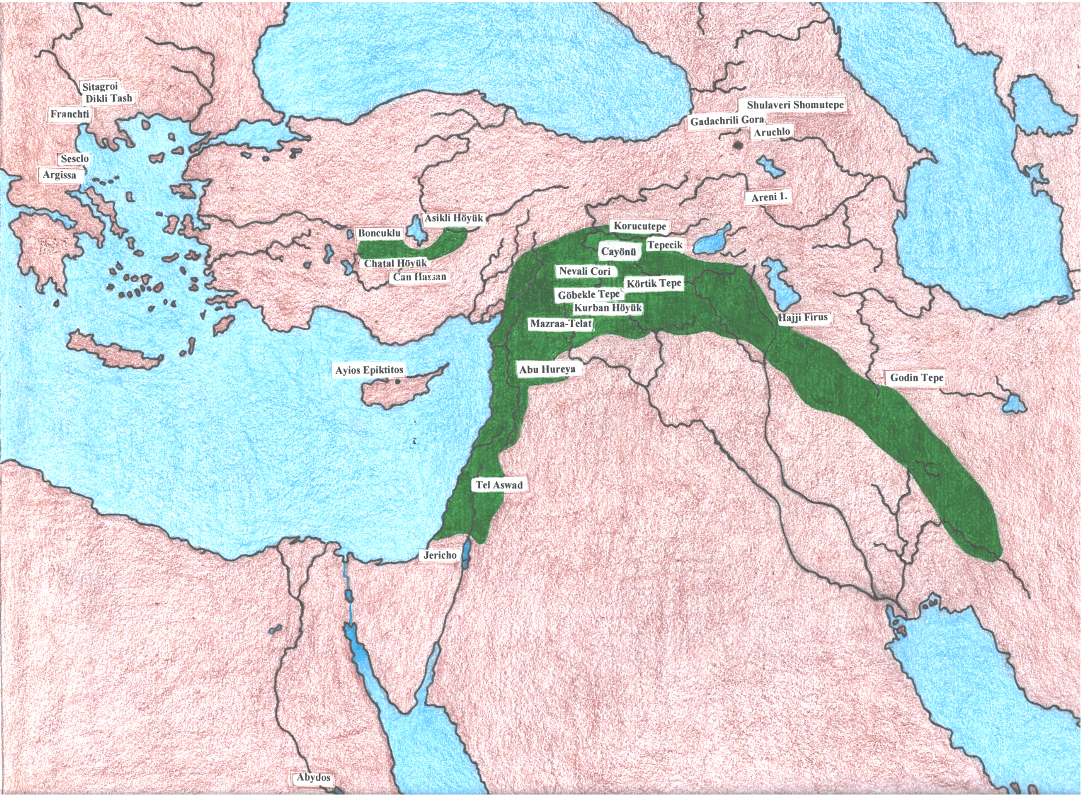

Göbekle Tepe liegt im Zentrum des sogenannten Fruchtbaren Halbmonds, der von Syrien über den Südosten der Türkei, Nordiran in den Zagros des Irak reicht. Hier gab es vor etwa 14 -10000 Jahren die größten Vorkommen an kultivierbaren Wildpflanzen und domestizierbaren Wildtieren. So wundert es nicht, dass in diesen Gebieten sehr frühe Spuren temporär und dann permanent besetzter Siedlungen gefunden wurden.

Ein lokal großes Vorkommen von Wildgetreide kann weder sofort konsumiert, noch in bedeutenden Mengen mitgenommen werden. So wurde der Überschuss an Wildgetreide anfangs in Erdlöchern gelagert und bewacht. Je größer der Getreidevorrat umso länger der Aufenthalt am gleichen Ort. Da sich Getreideernte und Lagerung im nächsten Jahr wiederholte, konnte man auch Wohnplätze und Lagerorte für eine Wiederbenutzung einrichten. Die Erfahrung, dass in Erdlöchern gelagertes Getreide nach einiger Zeit keimte, ließ nicht lange auf sich warten. Sie revolutionierte nicht nur die Wirtschaft der Sammler und Jäger, sie führte letztendlich auch zu einer Vielzahl von „Erfindungen“, die eine Aufbewahrung von Getreide und andere Nahrungsmittel betrafen. Möglicherweise wurden die Innenwände des Erdlochs anfangs nur mit feuchter Erde geglättet. Irgendwann nutzte man auch den geschmeidigen Ton und härtete die damit hergestellte Innenwand durch ein Feuer in der Erdhöhle. So konnte man im Erdtopf mit gehärteter Innenwand aus Ton das Getreide viel länger aufbewahren. Das Erlebnis des keimenden Korns, der Wiedergeburt der Getreidepflanze in einem Erdloch hatte auch weitreichende Folgen für die religiösen Vorstellungen der damaligen Menschen. Es ist deshalb nicht verwunderlich, dass in der Folge Verstorbene zur Sicherung der Wiedergeburt in diesen Getreidebehältern, später auch in Tongefäßen „beerdigt“ wurden.

Frauen pflanzten jetzt die Setzlinge des gekeimten Wildgetreides an geeigneten Stellen und wurden so unabhängig von dem begrenzten natürlichen Vorkommen des Wildgetreides. Damit begann der Prozess der „Neolithischen Revolution“, der Kultivierung und der Domestizierung bis hin zu Landwirtschaft und Viehzucht und ihre Verbreitung.

Die ersten Siedlungen

Die ersten, anfangs zum Teil noch temporär genutzten Siedlungen liegen mit ganz wenigen Ausnahmen im engeren Bereich des „Fruchtbaren Halbmonds“ Es sind primäre Orte des Wandels von der Wirtschaftsweise des Jagens und Sammelns zu Ackerbau und Viehzucht.

2. Fruchtbarer Halbmond, die wichtigsten frühen Siedlungen und Fundplätze von Trauben. Die Karte wurde aus folgenden Quellen zusammengesetzt: A) Mellaart, J. 1975 pp. 20 – 21, pp. 40-41. dito pp. 196-197. B) Wikipedia Karte Neolithic sites in Iran. C) www.oekosystem–erde.de.Karte 2

Zu ihnen gehören, von Westen nach Osten:

Abu Hureyra 13000 – 6000 v. Chr. erste Siedlung durchgehend bis zu den Anfängen des Ackerbaus besiedelt. 3, 4

Hallan Chemi 11700 – 11270, 9500 v. Chr. am oberen Tigris, erste Anzeichen des Übergangs zur Landwirtschaft und der Domestikation des Schweins. 5

Jerf el Amar 9600 – 8500 v. Chr. Erste Übergänge zur Landwirtschaft. 6

Körtik Tepe ab ca. 9300 v. Chr. ist eine der frühesten permanenten Siedlungen in West Vorderasiens. Ausreichende Nahrungsmittelproduktion und Lagerräume, Gewebe und zum Teil reiche Dekorationen auf Steingefäßen, sowie religiöse Riten weisen auf eine komplexe Gesellschaft. Da weder Tiere domestiziert noch Getreide kultiviert sind, bezeichnet man die Bewohner von Körtik Tepe als eine sesshafte Erntegesellschaft. 7

Göbekle Tepe 9000 v. Chr. und älter, Kultzentrum – keine Siedlung, zeitlich kurz vor dem Übergang zur Sesshaftigkeit. Große temporäre Tempelanlagen und Kulträume. 8, 9

Nevali Cori 8600 – 8000 v. Chr. Sesshaftigkeit und Übergang zum Ackerbau, Einkorn und Gerste, Linsen, Erbsen, Wicken, Mandeln und Trauben. Mehrere hundert Tonfiguren die mit einer Temperatur von 500-600 °C gebrannt waren, ein erster Ansatz zur Entwicklung der Brenntechnik für die Töpferei. 10, 11 (ancient-wisdom.co.uk)

Tell Mureybit 8050 – 7550 v. Chr. evtl. erste Kultivierung von Getreide, das erste Bier, ab 7350 v.Chr.. Rundbauten, ab 7000 v. Chr. erste rechteckige Häuser, Pflanzenbau. 12, 13

Asikli 9000 – 7500 v. Chr. liegt außerhalb und nordwestlich des eigentlichen Fruchtbaren Halbmonds auf 1400 Meter Höhe. Nördlichste frühneolithische Siedlung mit Übergang zum Pflanzenbau (und zur Viehzucht?), reiches Vorkommen an Getreidearten. Möglicherweise war das reiche Vorkommen qualitativ hochwertigen Obsidians der ursprüngliche Grund für das Entstehen der nur wenige Kilometer vom vulkanischen Hasan Dag und Göllü Dag entfernt liegenden Siedlung. Der Obsidianhandel scheint schon vor 10 000 Jahren aus dieser Region bis nach Jericho und auch Zypern geführt zu haben, da man dort den „Asikli Obsidian“ fand. Entsprechend wurde die Bezahlung in Form von Meeresschnecken in Asikli gefunden (Mihriban Özbasaran pers com). 14

Cayönü 7250 – 6750 v. Chr. Emmer und Einkorn kultiviert, Trauben und Feigen wild, Früchte des Zürgelbaums (celtis), Pistazien, Mandeln gesammelt, erste Versuche der Töpferei. 15, 16

Im Zagros, dem südöstlichen Teil des Fruchtbaren Halbmond

Zawi Chemi 10,600 v. Chr. Vorkeramische frühe Siedlung, Früchte des Zürgelbaums (celtis). 17

Jarmo 7000 v. Chr. älteste landwirtschaftliche Gemeinschaft, erste grobe Keramik pflanzlich gemagert. 18

Ganj Dareh 8000 v. Chr. die Ziege ist hier schon domestiziert. Erste Versuche der Töpferei. Große freistehende sonnengetrocknete Vorrats-Tonfässer. 19, 20

Ali Kosh 7500 v. Chr. Anfang des Getreidebaus im südöstlichsten Teil des Fruchtbaren Halbmond, Zagros. 21

In südwestlichen Ausläufer des Fruchtbaren Halbmonds

Ain Mallah 10,000 v. Chr. Rundhäuser und Vorratsgruben 80 cm tief mit weißem Putz ausgestrichen. Nutzung von Wildgetreide und Wildtieren. Frühester Hinweis auf die Domestikation des Hundes. 22, 23

Jericho ab 10,000 bis ca. 8,000 v. Chr. erste Anbau von Emer, Gerste und Hülsenfrüchte. Lange prähistorische Besiedlung. Berühmt durch großen Turm und Mauer. 24

Ain Ghazal 7,500 – 5000 v. Chr. sehr große prähistorische Ansiedlung, Anfang des Ackerbaus. 25, 26

Von diesen und einer Anzahl weiterer Orte in der Region breitet sich die Kenntnis der Domestizierung zuerst auf geeignete benachbarte Gebiete, in westliche und östliche Richtung aus. Mit dem neu erworbenen Wissen, einem Säckchen Getreidekörner und einigen gezüchteten Schafen oder Ziegen konnte man praktisch “ neue Welten“ erobern und dort sesshaft werden.

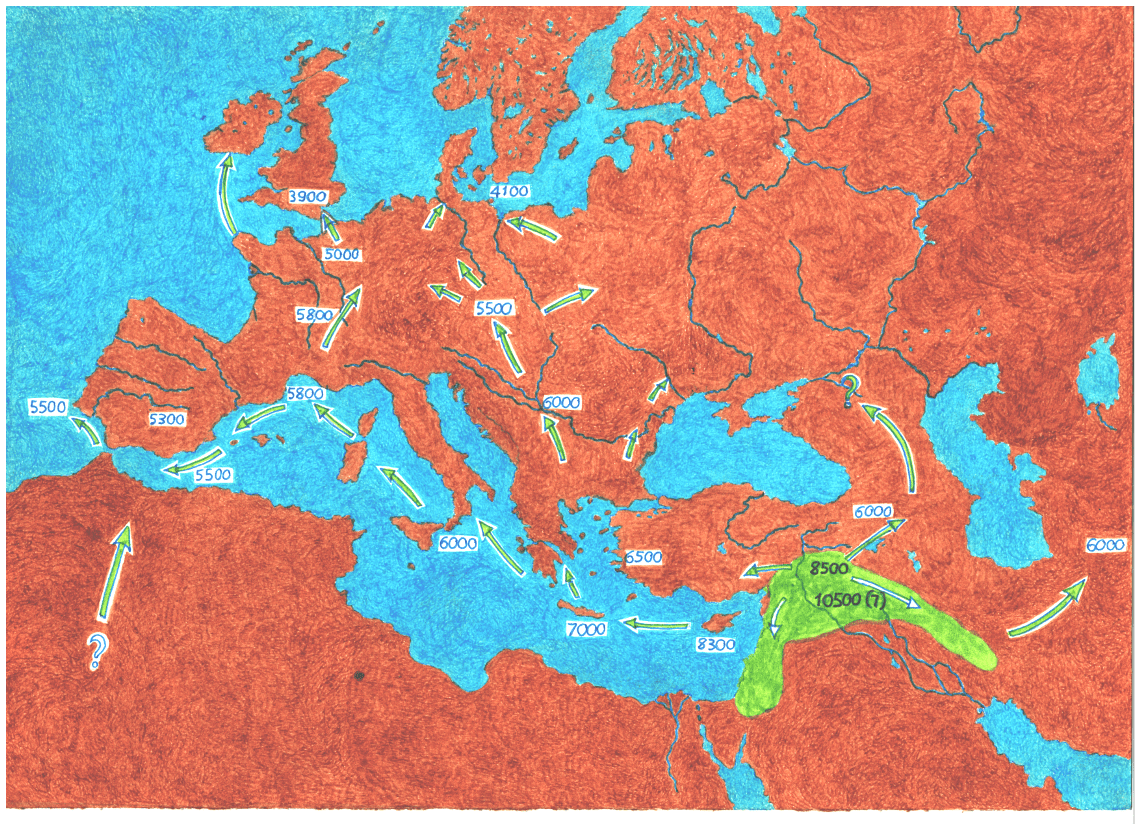

Verbreitungswege

Der Weg der frühen Bauern führte aus der Levante bereits etwa 8300 v. Chr. nach Zypern und gleichzeitig über Anatolien nach Griechenland und Bulgarien und von dort nordwärts, über den Balkan die Donau aufwärts bis nach Nordeuropa.

Die zweite Route führte über Griechenland nach Südostitalien und entlang der Küsten Spaniens, Portugals und Südfrankreichs nach Westfrankreich und über den Ärmelkanal.

Die dritte Route führte nach Armenien und Georgien und vielleicht in die östliche Ukraine

Die vierte Route führte über den Sinai nach Ägypten und Nordafrika.

Weitere Routen führten nach Südarabien, in den Iran, nach Afghanistan und von dort weiter nach Osten.

3. Fruchtbare Halbmond, Verbreitungswege und Verbreitungszeiten des Neolithikums. Diese Karte der Neolithisierung wurde nach: Studien zur Dynamik neolithischer Gesellschaften, Römisch-Germanischem Zentralmuseum Mainz, und Darstellungen der Ausbreitung des Neolithikums gezeichnet.

Viele frühe neolithische Siedlungen waren große Siedlungen, es gab noch keine Keramik. Hier war allerdings schon eine Organisation nötig, die alle Bereiche des Lebens betraf. In einem solchen Umfeld konnten einzelne Menschen aus der Nahrungsgewinnung herausgenommen und für andere Arbeiten freigestellt werden, zum Beispiel, für Kulthandlungen, oder auch zur Produktion von besonderen Produkten. Obwohl es schon früher verschiedene Versuche gab, kann man allgemein erst ab 6500 v. Chr. von brauchbarer Keramik, von einfacher Gebrauchskeramik bis zu Kultgefäßen sprechen. Hier begann das keramische Neolithikum.

Spätere neolithische Siedlungen

Dem zeitlichen Verlauf der Neolithisierung entsprechend entstanden später auch an anderen Stellen größere Siedlungen als sekundäre Orte der (Weiter-) Entwicklung von Ackerbau und Viehzucht.

Chatal Höyük ca. ab 7400 – 5400 v. Chr. 27, 28, Can Hassan ab 6500 v. Chr. 29, 30, Kösk Höyük 6300 – 5600 v. Chr. 31 und Hacilar 5400 – 5000 v. Chr. 32 sind die in Anatolien bekannte Orte der Neolithischen Revolution. Der Ackerbau wurde hier weiter entwickelt, möglicherweise wurde das Rind auch hier in Zentral Anatolien domestiziert, man wusste ja inzwischen wie das geht. In Catal Höyük fand man große Wandbilder, in Hacilar eine vielfältige und formenreichen Töpferei mit Kult- und Trinkgefäßen. Ortschaften mit bis zu 3000 Einwohnern belegen eine rasante wirtschaftliche und kulturelle Entwicklung. Ähnliche Entwicklungen fanden mit unterschiedlichen Zeitverschiebungen im Westen und im Osten statt.

Nördlich des Fruchtbaren Halbmonds, im südlichen Kaukasus sind besonders die neolithischen Siedlungen Aruchlo 33 und Gadrachili Gora ca. 5800 – 5200 v. Chr. 34 und Shulaveri ca. 5400 – 4200 v. Chr. 35 interessant. Während sich die westliche Ausbreitung von Ackerbau und Viehzucht archaeologisch gut nachvollziehen lässt, fehlt es an verlässlichen Forschungsergebnissen im Norden und im Osten. Die aktuellen Grabungsarbeiten in Aruchlo sollen Datierungen im Transkaukasus absichern und besonders die Kenntnisse über die frühen Bauern im Kaukasus erweitern.36

Aus dem Nordosten ist besonders Hajji Firuz 5400-5000 v. Chr. 37 und Godin Tepe 3500-3200 v. Chr. 38 bekannt.

Im Osten ist es Tepe Hissar ca. 4500-2000 v. Chr. 39 ein Ort sekundärer Entwicklung für Ackerbau und Viehzucht und der Nutzung lokaler Früchte wie Oliven, Trauben und anderer Pflanzenressourcen.

Ein Überblick

Die Vorratshaltung von getrocknetem Getreide, Hülsenfrüchten und anderen pflanzlichen Produkten (zuerst wild, dann auch kultiviert) fanden wahrscheinlich zuerst in Erdgruben und in anderen Behältern und Lagerplätzen statt. Hinzu kamen die Haltung und später die gezielte Züchtung von geeigneten Nutztieren. Beides hatte zum Ziel, zu jeder gewünschten Zeit pflanzliche und tierische Nahrung zur Verfügung zu haben.

Die Lagerfähigkeit von Nahrungsmittel zu verlängern (ist bis heute ein wichtiges Thema), und weitere Ressourcen zur Sicherung der Nahrungsversorgung zu erschließen, blieben in den folgenden zwei bis drei Jahrtausenden im Vorderen Orient die Hauptthemen der neolithischen Bevölkerung. Sie halfen nicht nur die steigende Zahl der Bevölkerung zu ernähren, sie ermöglichen auch Freiräume für die Entwicklung von Kult und Kultur zu schaffen.

Erste Gottheiten, verantwortlich für Fruchtbarkeit und Wiedergeburt, dann für Fruchtbarkeit und Wetter, und schließlich für Fruchtbarkeit und Kriegsglück wurden greifbar. Die heilige Hochzeit wurde in Variationen gefeiert, bis der König, schließlich über der Priesterin stehend, als Vertreter Gottes gefeiert wurde. Diese wenigen Zeilen stehen für 6000 Jahre vorgeschichtliche Entwicklung und Veränderung, in denen die Töpferei einen immer bedeutenderen Platz einnahm.

Gegen Ende des vorderasiatischen Neolithikums lösten sich viele der Großsiedlungen auf. Die Folgezeit heißt Chalkolithikum, Kupferzeit und dauerte im Vorderen Orient etwa 1000 Jahre an. Die wachsende Bevölkerung breitete sich in alle Richtungen aus. Es entstanden fast überall, da wo gute Wirtschaftsflächen vorhanden waren, kleine und kleinste Siedlungen. Es waren einfache Bauern und Viehzüchter, die inmitten ihrer Felder und Weiden lebten. Hier fand man bei Ausgrabungen nur einfache, grobe Keramik für den täglichen Gebrauch, einige kleine Kultfiguren, Schalen und nur selten etwas größere, leicht tragbare Vorratsbehälter.

Vom Dorf zum Wirtschaftszentrum, die Entwicklung des Handels mit anderen Zentren und Regionen, die Domestizierung von Oliven, Datteln, Feigen und Trauben

Von der zweiten Hälfte des Chalkolithikums an veränderte sich wieder die Siedlungsweise. Neben vielen Dörfern entstanden eine Anzahl von größeren Siedlungen und schließlich auch Handelszentren. Später, im Übergang vom Chalcolithicum zur Bronzezeit, erwachsen daraus Fürstentümer, Stadtstaaten und Königreiche und es entsteht die Schrift. Der Bedarf an einfachster Gebrauchskeramik, von kleinen und großen Gefäßen zur Lagerung von Nahrungsmittel bis hin zu aufwendigen Kultgefäßen, wächst mit der Größe und der Bedeutung dieser Zentren. Einen besonderen Bereich nehmen Weiheschalen und Trinkgefäße in Tierform, Gefäße zum Mischen von Weihegetränken und große Behälter zur Lagerung von Öl, Bier, Wein, Getreide, Fleisch, Früchten, Wasser usw. ein. Ihnen gilt auch ein großer Teil der frühen Schriften. Hier wird ausführlich erklärt und aufgezählt, wie die verschiedensten Gottheiten als oberste Herrscher und Schützer angerufen und ihnen Weihe-Speisen und Weihe-Getränken geopfert werden müssen.

Konnten Bauern sich bisher neben angebauten Gemüse und Getreide noch mit Wildfrüchten und anderen Wildpflanzen versorgen, so stieg in den Großsiedlungen der Bedarf besonders an Früchten und deren Produkte schnell an. Wie Margarete Tengberg in ihrer Arbeit darstellt, fand die Domestikation der ersten Fruchtbäume, nämlich Oliven, Feigen, Datteln und Trauben, im späten Chalkolithikum statt. In dieser Zeit waren auch alle Voraussetzungen für eine erfolgreiche Weinproduktion gegeben. Zwar hält M. Tengberg eine etwas frühere Kultivierung von Trauben für nicht ausgeschlossen, doch bleibt offen, ob das Endprodukt dann schon Wein war. 40

Da man allgemein große Tongefäße gerne mit Wein oder seinem Herstellungsprozess in Verbindung bringt, möchte ich hier eine Reihe früher Funde von Trauben (Vitis vinifera) auflisten.

Die wichtigsten Funde der Traube (Vitis vinifera) aus vorgeschichtlicher Zeit

1 Tell Abu Hureya, am Euphrat in Syrien, 13 000 – 9500 v.Chr.

Traubenkerne von Vitis vinifera ssp.sylvestris. 41

2 Terra Amata, bei Nizza, Frankreich, 11 000-8000 v.Chr.

Traubenkerne von Vitis vinifera ssp.sylvestris. 42 Aus dieser Höhle kennt man die frühesten menschlichen Siedlungen, datiert auf 380 000 v. Chr. (eine andere Datierung ist 230 000 v. Chr.) 43

3 Franchti Höhle, Argolid, Griechenland, 11 000 v.Chr.

Traubenkern von Vitis vinifera ssp.sylvestris. 44 Es handelt sich hier allerdings um nur 1 Traubenkern der Wildtraube, der aus diesem Zeitraum in dieser Höhle gefunden wurde. Die Höhle wurde über viele Jahrtausende immer wieder benutzt (siehe weiter unten). Die Franchti Höhle liegt im bekannten Verbreitungsgebiet von Vitis, v. sylvestis, der Wildtraube.

4 Grotta del`Uzzo, Sizilien, Italien, 10 000 v.Chr.

Traubenkerne von Vitis vinifera ssp.sylvestris. 45

5 Körtik Tepe, Südost Anatolien, Türkei, ca. ab 9600 v. Chr.

Kleine, aber kulturell reiche sesshafte Bevölkerung, die Wildtiere jagte, fischte und auch Pflanzenressourcen sammelte. Ein sesshaftes Erntevolk. Sekundärbegräbnisse, gereinigte und bemalte Knochen und unterschiedlich ausgestattete Begräbnisse weisen auf eine hierarchisch organisierte Sozialordnung. 46 Hier wurde in zwei Steinschalen Weinstein gefunden.47 McGovern folgerte, dass in diesen Gefäßen Wein war.48

6 Tell Aswad, Syrien, 9500-8700 v. Chr.

Traubenkerne von Vitis vinifera ssp.sylvestris. 49

7 Jericho, Palestina , 9600-9000 v. Chr.

Traubenkerne von Vitis vinifera ssp. Sylvestris. 50

8 Göbekle Tepe 9000 v. Chr. und älter,

Kultzentrum mit monumentaler Architektur, aber keine Siedlung, zeitlich kurz vor dem Übergang zur Sesshaftigkeit . 51, 52 Neben den „Tempelhallen“ fand man Arbeitsräume, vereinzelt mit großen Steinschalen. In ihnen wurden keine Traubenreste, aber Hinweise auf Rückstände von Bier gefunden. Im Oktober 2013 besuchte ich wieder Göbekle Tepe. Die Ausgrabungen hatten weitere Stelen und auch Räume ans Licht gebracht. In zwei Räumen konnte ich recht große Steingefäße sehen (ca.160 Liter Fassungsvermögen) die, so vermutet das Grabungsteam, für Bier verwendet worden waren. Ein großer Knochen, auf dem Boden eines der großen Gefäße war vielleicht zum Rühren des Biers verwendet worden. 53 Etwas unterhalb der ausgegrabenen Tempel gibt es einen großen geglätteten Felsboden. Hier sind zwei runde Wannen aus dem Fels geschlagen. Zwischen den Wannen, sie können mindestens 3000 Liter fassen, ist der Boden mit einer größeren Zahl flacher Vertiefungen übersät, sie ähneln kleinen Schalen. Hier konnte man Gerste quetschen und leicht keimen lassen und dann zur Gärung und zum Brauen des Biers in die Steinwannen geben. Da sicherlich hunderte Menschen am Bau der Anlage und dann auch an den Kulthandlungen und Tanzfesten beteiligt waren, konnte diese Bierbrauerei mit den beiden Wannen den Bedarf für 2-3 Festtage sicher produzieren. Sollte es sich hier wirklich um eine Bierbrauerei handeln, so wird eine Weinherstellung im Neolithikum unwahrscheinlich. Das Kultgetränk Bier kann ganz einfach im Rahmen der täglichen Verwendung mit Getreide hergestellt werden. Für die Herstellung von Wein braucht man mindestens eine über die Subsistenzwirtschaft hinausgehende wirtschaftliche Situation, sowie dichte und gut verschließbare Gefäße. Diese Voraussetzungen sind in frühen neolithischen Siedlungen nicht vorhanden.

9 Nevali Cori, Südost Anatolien, Türkei, 8,600 – 8,000 v.Chr.

Befund: Sesshaftigkeit und Übergang zum Ackerbau. Einkorn bildet das häufigste kultivierte Pflanzengut. Danach folgt der zweikörnige Weizen. Gerste konnte nur in seiner wilden Form nachgewiesen werden. Linsen, Erbsen, Wicken und andere Hülsenfrüchte ergänzten das Nahrungsangebot, wie auch gesammelte Pistazien, Mandeln und Trauben. Zum Aufbewahren von Nahrungsmittel gab es diverse Behälter, auch aus Stein, aber noch keine Keramik. 54, 55

10 Cayönü, Südost Anatolien, Türkei, 7500-5800 v. Chr.

Aus dem Zeitraum von 7250 – 6750 B.C. fand man Emer und Einkorn kultiviert. Wilde Trauben und wilde Feigen, Früchte des Zürgelbaums (Celtis) Pistazien und Mandeln wurden gesammelt. Es gab erste Versuche der Töpferei. 56, 57 Cayönü wurde in der frühen Phase der Neolitisierung etwa 2000 Jahre bewohnt. Interessant ist die umfangreiche Nutzung von Wildfrüchten, besonders der Früchte des Zürgelbaums (Celtis), aber auch Trauben und Feigen. Wurden sie als Getränk oder als Nahrungsmittel aufbereitet und verwendet? Erste Versuche der Töpferei, vielleicht zur Verbesserung der Lagerhaltung, wurden anfangs in Cayönü zwar begonnen, dann aber wieder aufgegeben. Erst aus der letzten Phase der langen Besiedlung kennt man eine einfache grobe Keramik. 58, 59

11 Jiahu,Yellow River Valley, China, 7000 – 6600 v.Chr.

“The Earliest Alkoholic Beverage in the World”.

Chemische Analysen von Rückständen in Tongefäßen, die bei Ausgrabungen der neolithischen Siedlung Jiahu in China gefunden wurden, zeigten, dass hier schon im 7.Jahrtausend v. Chr. ein fermentiertes Getränk aus Reis, Honig und Früchten, (Weißdorn oder Trauben) hergestellt worden war. 60 Die Analysen ergaben Weinsäure. Diese kommt jedoch in allen Traubenprodukten (Rosinen, Essig, Traubensirup) und in großem Umfang auch in Weißdorn und anderen Pflanzen vor. 61 Deshalb ist Weinsäure noch kein sicherer Beleg für Wein oder ein anderes fermentiertes Getränk. 62, 63 Allerdings ergibt Reis (und auch anderes Getreide), zusammen mit Honig und dem Zusatz von ein oder zwei Früchten, eine nahrhafte Speise, die wenn man etwas wartet auch fermentiert. Ein solches Produkt ist dann breiartig und entsprechend eher essbar als trinkbar. Ich habe diesen frühesten Fund eines „fermentierten Getränks“ aus China in diese Liste hinzu genommen, weil Mischungen aus verschiedenen Früchten mit Getreide und Honig auch aus dem Vorderen Orient bekannt sind.

12 Chatal Höyük, Zentralanatolien, Türkei, 7400- 6200- 5400 v.Chr.

Chatal Höyük ist eine der größten und interessantesten neolithische Siedlung im Vorderen Orient. Die wichtigsten Getreidearten und Hülsenfrüchte sind kultiviert. Wildsammlungen, darunter auch Früchte ergänzen das Nahrungsangebot. 64, 65, 66 James Mellaart, der in den 60iger Jahren Chatal Höyük als bis dahin größte (ca.2500-5000 Einwohner) und spektakulärste neolithische Siedlung ausgrub, war ein hervorragender Kenner neolithischer Keramik. Die frühen Keramiken sind in vielen neolitischen Siedlungen sehr ähnlich. Sie sind noch sehr grob und die frühen Formen entsprechen in den meisten Fällen der Form, die man erhält, wenn man Vorratsgruben ausgräbt und ihre Wände verfestigt. Auch der aus neolitischer Zeit stammende in Georgien gefundene „Weintopf“ (5800 v.Chr.) hat die gleiche Form und Qualität. Zwar konnte man in diesen neolithischen Gefäßen Flüssigkeiten erhitzen, aber fermentierte Fruchtweine nicht über eine längere Zeit aufbewahren.

13 Can Hassan, Zentralanatolien, Türkei, etwa ab 7200-6500 v. Chr.

Befund: Weizen, Emmer, Einkorn, wild und kultiviert, Gerste, Zürgelfrucht, Wildtraube, Pflaume, Weißdorn, Nüsse etc. 67 Ein typisches Beispiel einer größeren neolithischen Siedlung. Wichtigste Ressourcen der regionalen Flora sind genutzt, obwohl noch nicht alle kultiviert sind. Die meisten Früchte, einschließlich Trauben, wurden ebenfalls in so großem Umfang verwendet, dass sie nach den Ausgrabungen als wichtige Nahrungsmittel eingestuft wurden. 68, 69

14 Argissa, Achilleion und Sesclo, Griechenland, 6400- 5300 v.Chr.

Bei den Ausgrabungen dieser drei neolithischen Siedlungen wurden Traubenkerne von V.v. sylvestris gefunden. 70 Die Ausgrabungen ergaben sehr deutliche Hinweise auf die wirtschaftliche Nutzung der Wildtrauben. Ob man daraus jedoch Wein gemacht hat, ist unbekannt und wenig wahrscheinlich, da sowohl die Töpferei (es fehlte an dichten und fest verschließbaren Töpfen), als auch das soziale Umfeld noch nicht die geeigneten Voraussetzungen boten.

15 Shulaveri-Shomutepe -Kultur Georgien, Azerbaidschan 5800-5400 v. Chr.

Dieser Kultur werden die frühneolitischen Siedlungen Aruchlo I., Dangreuli gora, Shulaveris gora, Gadachrili gora, Imiris gora, Chramis Didi gora im heutigen Georgien und Shomutepe, Babadervish, Tojretepe, Gargalartepesi, Geoytepe, Chalagantepe und Kültepe I. im heutigen Azerbaidschan zugeordnet. Die Shulaveri Siedlungsgruppe wurde bei Grabungen in 1965–1971 entdeckt. 7, 72 Die in Chramis Didi Gora gefundenen karbonisierten Traubenkerne lassen, so die georgischen Fachleute, den Übergang von der wilden zur kultivierten Form erkennen. Darüber hinaus wurden die in Shulaveris Gora und in Dangreuli Gora gefundenen Traubenkerne als kultiviert bestimmt. 73 In Dangreuli Gora wurden 6 Traubenkerne auf dem Boden, in Shulaveri Gora 4 Traubenkerne in Haus No.1 gefunden. Neuere Ausgrabungen eines georgisch-deutschen Grabungsteams haben zu diesen neolithischen Siedlungen wichtige neue Befunde erbracht.74

16 Gadachrili Gora, Georgien: cal. 5780 v. Chr.

2006 wurde die Ausgrabung in Gadachrili Gora wieder aufgenommen. Befund: Verschiedene Rundbauten mit einem Durchmesser von 1,5 bis 2,5 Meter aus ungebrannten Lehmziegeln (Adobe, Kerpitch), Fragmente von Tongefässen, typisch für die Shulaveri- Shomutepe- Kultur, sowie Geräte aus Stein, Knochen und Horn. In 2007 wurden Kulturpflanzen (Getreide, Trauben u.a.) identifiziert. Verschiedene Tonscherben wurden chemisch untersucht und das Vorhandensein von Weinsäure festgestellt. M. Jalabadze und seine Kollegen und Kolleginnen meinen, dass der Ursprung der Weinsäure Wein oder (süsser) Traubensaft gewesen sein muß. Eine Radiokarbondatierung von Getreidekörnern ergab cal. 5783 +- 42 v. Chr. Sie führen weiter aus: “Es wurden viele Pollen der kultivierten Rebe gefunden sowie Pollen der für Weingärten typischen Unkräuter. In dem Belag einer Keramikscherbe wurden die Pollen der kultivierten Weinrebe gefunden, was davon zeugt, dass in dem Gefäß Wein war. Da die gefundenen Keramikfragmente eine grobporige Struktur haben, konnte die (Wein) Flüssigkeit diese Poren tief durchtränken und sich nicht nur an den Innenwänden des Gefäßes, sondern auch in den Poren absetzen“. 75

17 Aruchlo: Georgien 5800 v. Chr. cal.

Die Siedlung besteht aus Rundbauten diverser Größe. Es fehlen jedoch feste Kocheinrichtungen (bis auf wenige offene Feuerstellen), wie man sie aus neolithischen Häusern erwartet. Es ist deshalb eine Hypothese, dass es sich bei der Siedlung in Aruchlo um eine saisonale Besiedlung handelt.. Aruchlo war von etwa 5800 bis 5400 besiedelt. Danach war der Ort für längere Zeit unbewohnt. Erst zum Anfang des 4ten Jahrtausends erscheinen neue Bauformen (Kurgan), Metallwaffen und symbolische Objekte einer neuen Elitegruppe. 76,77 Der von Anfang an vorhandene Haustierbestand, sowie die meisten kultivierten Getreidesorten und Hülsenfrüchte sind von den Siedlern wahrscheinlich aus dem Süden oder dem Osten mitgebracht worden. Die meisten der gefundenen Tongefässe der Shulaveri-Shomutepe Kultur sind grob und noch nicht mit hoher Temperatur gebrannt, Feuerspuren sind zu erkennen. Ca 90% der Scherben stammen aus neolithischer Zeit. Ein Teil der Keramik hat ein einfaches Knubbendekor. Bei einem der größeren Töpfe waren Knubben in einer Form zusammengesetzt, die an Trauben denken lässt. Die Shulaveri Keramik wird mit ostanatolischer Knubben – Keramik in Verbindung gebracht. 78

4. Tongefäß mit Trauben Darstellung, neolithisch, ca. 5600 v.Chr. National Mus. Tiflis, Georgia.

18 Hajji Firus Tepe, Nördlicher Zagros, Iran, 5400 – 5000 v. Chr.

war eine kleine „sekundär- neolithische“ Siedlung. Erste Kenntnisse der neolithischen Wirtschaftsweise wurden aus dem Fruchtbaren Halbmond kommend hier hin gebracht und dann regional weiter entwickelt. Mary M. Voigt leitete 1968 eine Grabungsexpedition Hajji Firuz, Iran. Die Funde wurden zwischen dem Iran und dem Penn Museum aufgeteilt. 79 25 Jahre später konnte Patrick E. McGovern zwei Keramiktöpfe aus Hadjji Firuz untersuchen und Hinweise auf eine Verwendung von Trauben belegen. Hier einige Auszüge aus seinen anschließenden Publikationen: 80, 81, 82, 83 Es ist hier von einem einfachen normalen neolithischen Wohnhaus die Rede, nicht von einem Kultraum, einer Tempelanlage oder einem herrschaftlichen Wohnsitz. In zwei von 6 vorhandenen Krügen fand man Rückstände, in den anderen nichts. Ofen und Küchengeräte befanden sich an der Wand und wiesen diesen Raum wirklich als Küche eines Wohnhauses aus. Was macht Wein in einer Küche, da man doch in der Vor- und Frühgeschichte Wein nur aus den Lageräumen von Eliten kennt? Den Keramiktöpfen wurden einige im Raum gefundene Deckel (Lehmstopfen?) mit einem geschätzten Durchmesser von 10-15 cm, passend zum Tontopf zugeordnet. Doch die Tontöpfe dieser Zeit leckten, sie konnten zwar verschlossen, aber, soweit erkennbar nicht wirklich abgedichtet werden.

.

19 Ayios Epiktitos Vrysi, Zypern, ca. 5350 v.Chr. (besiedelt bis 3000 v. Chr.).

In der frühen Phase Getreide, Hülsenfrüchte, Trauben, Oliven, voll entwickelter Ackerbau. Dies sind die bisher frühesten Hinweise für die Nutzung der Trauben auf Zypern. 84 Für die Verwendung der Trauben gibt es keine speziellen Hinweise. So kann man davon ausgehen, dass sie als Nahrungsmittel, getrocknet, auch als eingedickter Saft haltbar gemacht, oder in anderer Form genutzt wurden.

20 Sesclo, Sitagroi, Dikli Tash, Dimitria. Griechenland, 6500 – 4300 – 2800 v. Chr.

In Sesclo fand man aus der Periode von 6400-5300 v. Chr. Traubenkerne der wilden, Vitis vinifera sylvestris, Form. Um etwa 4300 fand man in Sitagroi, Dikli Tas und Dimitria erste Hinweise auf möglicherweise domestizierte Trauben. In der Zeit zwischen 4300 und 2800 v. Chr., wurden in diesen vier Siedlungen Traubenkerne und Geräte, die auf eine Verarbeitung von Trauben (zu Wein?) hinweisen, in größerer Anzahl gefunden. Durch die ausreichend großen Anzahl von Traubenkerne konnten Kerne von wilden und kultivierten Trauben definitiv unterschieden werden. 85 Die Keramik hat zu dieser Zeit schon eine hervorragende Qualität, in ihr konnte man Flüssigkeiten längere Zeit aufbewahren.

21 Dikli Tash, Griechenland, Kavala um 6500 – 4000 v. Chr.

Frühester Fund gepresster Trauben (Vitis vinifera), 2460 Traubenkernen zusammen mit 300 Traubenschalen, wurde auf 4200 v. Chr. datiert. Auf einigen Traubenkernen fand man noch die Reste von Traubenschalen, ein Hinweis, dass die Trauben gepresst wurden, um den Saft zu gewinnen. In der Nähe der Traubenreste wurden Tongefäße gefunden, die für Trauben oder Saft geeignet waren. Warum in weiteren drei untersuchten Räumen keine weiteren Traubenreste gefunden wurden, konnte noch nicht geklärt werden. 86 Neben den Traubenresten wurden auch Feigen gefunden. Da der Saft von wilden Trauben oft einen bitter-sauren Geschmack hat, kann es sein, dass man Feigen dem Traubensaft zugefügt hat, um den Geschmack zu verbessern. 87 In 2013 wurden die Resultate der Untersuchungen der Keramiken beendet, in denen zum Teil Traubenreste gefunden wurden. 88 89

22 Tepecik Höyük, Osttürkei, 4500-3500 v.Chr., Beginn des Chalkolithikums

Domestizierte Vitis möglich.90 Kein Hinweis auf Wein.

23 Korucutepe, Osttürkei, 4500-3500 v. Chr.

Traubenkerne von Vitis vinifera ssp.sylvestris. 91

24 Franchthi Höhle-Argolid Griechenland, 4300 -2800 v. Chr.

In dieser berühmten Höhle, in der man schon im Paleolithikum Trauben verwendet hat, fand man auch in den folgenden Zeitabschnitten, besonders ab dem Chalkolithikum, zunehmend Reste von Trauben und Kernen. Ab der gleichen Zeit (4300 – 2800) trifft man auch bei vielen anderen Ausgrabungen in Griechenland (Arapi, Simini, Sesclo, Pefkakia, Dimitra and Dikli Tash) auf große Mengen Traubenreste.92

25 Sitagroi III, Griechenland, 4300 – 2800 v. Chr.

In Sitagroi wurde die Unterscheidung von Wildtrauben und domestizierten Trauben durch die sehr große Anzahl von Kernen beider Sorten sehr erleichtert. 93 Hier kann man sicher schon eine wirtschaftlich orientierte Produktion annehmen. Doch warum und für was nutzt man wilde Trauben wenn man schon domestizierte hat?

26 Areni 1. Höhle, Südost-Armenien , um 4100 v. Chr. (spätes Chalkolithikum)

Die in 2010 abgeschlossene Ausgrabung einer „Weinkelterei“ in der Areni Höhle weist auf die Bedeutung dieser Region für eine frühe Weinproduktion hin. Der Fundort liegt 300 km nördlich von Hajji Firuz Tepe. 94, 95 Bei den Ausgrabungen wurde eine kleine wannenförmige Fläche für das Quetschen von Trauben, größere, im Boden eingelassene Tonfässer und zahlreiche Traubenreste und Trinkgefässe gefunden (4223-3790 cal v.Chr.). Die archäologischen, chemischen und botanischen Untersuchungen belegen die Verarbeitung von kultivierten Trauben und mit sehr hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit die Produktion von Rotwein. G. Areshian, Co-Direktor der Ausgrabung meinte, dass es zu dieser Zeit keine Möglichkeit gab, Saft ohne Fermentierung zu konservieren und jeder unfermentierte Saft sofort sauer wird…deshalb, so folgert er, muss der Inhalt mit großer Sicherheit Wein gewesen sein.96

27 Godin Tepe, Westlicher Zagros, Iran, 3500 – 3100 und 3100-2900 v. Chr. (insgesamt besiedelt von ca.5000-1600 v. Chr.)

Im auslaufenden Chalkolithikum und Übergang zur Bronzezeit sind alle Voraussetzungen gegeben, um Wein zu produzieren. Sumerische und Elamitische Stadtstaaten wurden gegründet, die Handelswege stark ausgeweitet. Die politische und kulturelle Stabilität ermöglicht eine rasante Wirtschaftsentwicklung. Godin Tepe wuchs in dieser Zeit zu einem der größten Orte in der Region.Godin Tepe war von ca 5000 bis etwa 1600 v. Chr. besiedelt. Die hier besprochenen Funde stammen aus der frühen und der späten Periode V. Die Tongefässe aus der frühen Periode V. fassen etwa 70 ltr, die aus der späten Periode V. 31-38 ltr. Alle haben etwa die gleiche Form. Ihre Öffnungen haben einen Durchmesser von ca. 12 cm, der Hals ist etwa 6 cm lang. Ein Gefäß war innen mit einer feinen Lage Ton geglättet, wahrscheinlich um den Topf besonders gut zu dichten. An einem der Gefäße aus der späten Periode V befand sich etwa 9 cm über dem Boden ein kleines Loch (zum einfachen Ausgießen des Inhalts?). Zwei U förmige Schnurformen dekorierten das Gefäß. Sieben Tonstopfen wurden bei den Ausgrabungen der Periode V. gefunden und Spuren solcher Stopfen an der Innenseite einiger der Tongefäße. Ein weiterer Hinweis ist der Fund eines fast kompletten Trichters mit einem Durchmesser von ca. 50 cm. sowie ein Deckel mit einem Gewicht von etwa 1 kg. Man vermutet, dass mit dem schweren Deckel die Trauben im Trichter gepresst wurden (ähnliche Trichter wurden in Kurban Höyük, Arslantepe, Türkei und Tel Barak, Syrien gefunden). Obwohl keine Traubenkerne oder andere Traubenreste gefunden wurden, nimmt man an, dasss ein 6-8 cm hohes Bassin, 50 x 50 cm groß, zum Quetschen der Trauben verwendet wurde. In der späten Phase V. sind die Räumlichkeiten ganz anders genutzt. In den Räumlichkeiten wurden nur noch 2 Tongefäße gefunden. V. R. Badler meinte abschließend, das diese archäologischen Funde auf die Existenz vom Wein in Godin Tepe hinweisen, was schließlich durch chemische Untersuchungen an Rückständen aus einigen der Tongefäße bekräftigt wurde. 97 Alle Funde und die Resultate chemischer Untersuchungen können allerdings auch als Beleg für die Herstellung von Traubendicksaft genommen werden.

28 Kurban Höyük, Südost Türkei, spätes 4tes bis frühes 2tes Jht, v. Chr. Bronzezeit

Ab der frühen Bronzezeit ist die Weinproduktion weit verbreitet und archäologisch, sowie auch schon schriftlich belegt. Die Funde von Traubenkernen und Pressresten nehmen über einen Zeitraum von etwa 1000 Jahren in Kurban Höyük so stark zu, dass man schließlich von einer Industrie sprechen kann. Offen bleibt, ob mit den Trauben „nur“ Wein, oder auch andere Produkte hergestellt wurden. 98, 99

29 Abydos, Ägypten, 3150 v. Chr., Grab des Scorpin I. der Dynastie 0

In Ägypten gab es keine wilden Trauben. Kultivierte Trauben wurden erst später eingeführt und dann in steigendem Umfang angebaut. Ägypten war wie Mesopotamien ein Land der Biertrinker. Die im Grab von Scorpion I. gefundenen 700 Amphoren mit einem Gesamtgehalt von ca. 4500 Liter geharztem Wein mussten damals von der Levante über viele hundert Kilometer bis zum Nil transportiert werden. Es war eine Grabbeigabe die zu dieser Zeit nur Herrschern vorbehalten war und wahrscheinlich auch nur von ihnen finanziert werden konnte. Die Untersuchung der Weinrückstände zeigten, dass neben Harz auch verschiedene Kräuter, wahrscheinlich Bohnenkraut (savory), Wermut (wormwood), Koriander (coriander), Minze (mint), Salbei (sage), Thymian (thyme) dem Wein zugemischt waren. 100, 101, 102

Diskussion zum neolithischen Wein

Im Zentrum dieses Artikels sollten große Tongefäße stehen. Aber obwohl diese Gefäße sehr vielfältig genutzt werden, denkt man fast immer zuerst an ihre Verwendung für Wein. Und immer wenn es um Wein geht, wird es besonders spannend, da Winzer, Weingenießer und Nationalisten mitfiebern, wo denn nun die Wiege des Weines lag. Jede neue Ausgrabung zwischen Südeuropa und China lässt auf neue Erkenntnisse hoffen.

Werden bei archäologischen Ausgrabungen Traubenreste gefunden, werden diese meist als ein Hinweis auf Wein interpretiert. Dass westliche Wissenschaftler in ihren Publikationen bei Trauben fast ausschließlich an Wein denken, hat wohl den Hauptgrund in der Sprache und Kultur. Den Traubengarten nennen sie Weinberg, Trauben sind stets Weintrauben, und sie schließen von Weinstein und Weinsäure auf Wein, obwohl diese nicht nur im Wein oder in Trauben vorkommen. Dies erklärt sich wohl vor allem daher, dass man in Westeuropa und Amerika weder eine Trauben- noch eine alte Weingeschichte hat. Man hat nicht Trauben kultiviert und Wein entwickelt, sondern alles schon fertig bekommen, zusammen mit den entsprechenden Begriffen. Dass in den Anfängen wahrscheinlich ganz andere Produkte aus Trauben (und anderen Früchten) im Vordergrund standen, dessen sind sich die Weinwissenschaftler nur sehr selten bewusst. Im Vorderen Orient hingegen ist die Traube weder sprachlich noch kulturell auf die Verwendung als Weintraube zur Weinbereitung fixiert. Hier wird die Traube auch immer noch traditionell sehr vielfältig verarbeitet und konsumiert.

Argumente die gegen die Existenz von Wein im Neolithikum sprechen

– Für die neolithische Subsistenzwirtschaft war Wein kein wichtiges Nahrungsmittel.

Die Herstellung nahrhafter Lebensmittel gehört zu den wichtigsten Zielsetzungen. Ein weiterer wichtiger Aspekt ist die Lagerfähigkeit, d.h. die Sicherung der Nahrungsmittel über einen möglichst langen Zeitraum. In einer kleinen Gemeinschaft mit einfacher Subsistenzwirtschaft gibt es kaum einen Spielraum für aufwendige Versuche der Domestikation und lange Wartezeiten bis zur Nutzung von Produkten mit geringem Nahrungswerten, wie es für Wein zutrifft und den man dann auch nur einmal im Jahr trinken kann, weil er schnell verdirbt.

Wilde Feigen, wilde Trauben, und andere Früchte, sowie wilde Pistazien, Mandeln und die Früchte des Zürgelbaums (Celtis) wurden frisch oder getrocknet und vielleicht auch als Bestandteil von Getränken lange vor dem Neolithikum bereits genutzt. Im Neolithikum war Bier als Kultgetränk schon vorhanden. Man konnte es zu jeder Zeit herstellen und zu jeder Zeit frisch trinken.

– Für Wein gab es Im Neolithikum nicht die entsprechenden Gefäße

Die meisten der Gefäße aus dem frühen keramischen Neolithikum waren noch sehr grob und sie waren nicht verschließbar. Ihre anfängliche Form der etwas größeren Behälter entsprach der Form früher Erdgruben zur Lagerung von Nahrungsmittel. Der Gefäßrand war dünn, es fehlt eine enge Öffnung oder eine breite Lippe, die für ein gutes Verschließen mit einem Lehmstopfen oder einem Deckel notwendig sind. L.C. Thissen schreibt über die Entwicklung der Keramik folgendes: „Obwohl die Brenntechnik vorher entwickelt wurde, entstand Keramik erst um 7000 v. Chr. Nach einer längeren Experimentierphase findet man in Chatal Höyük eine gute Keramik, allerdings noch mit Häckselmagerung. Um 6800 B.C. ist der Übergang zur mineralischen Magerung vollzogen, man konnte jetzt Gefäße mit dünneren Wänden herstellen. Gefäße aus der Zeit um 6600 B.C. besaßen kleine durchlochte Griffe und einen verbreiteten Rand. Diese Töpfe wurden zum Kochen verwendet. Etwa um 6300 B.C. begann man die ersten Töpfe mit applizierten Schnur- und Knubbelleisten zu produzieren. Eine frühe Reliefkeramik fand man in Kösk Höyük 6000 – 5700 v.Chr. mit mittelgroßen über 50 cm hohen Tongefässen“. 103 In diesen Gefäßen konnte man zwar Fruchtmaische gären lassen, doch ebenso schnell wie aus Maische ein alkoholischer Brei wird, wandelt er sich, ohne Schutz vor Sauerstoff, zu einem oxidierten, dem Essig ähnlichen Produkt. Tontöpfe werden erst ab einer Brenntemperatur von 1000 °C dicht, es sei denn sie wurden innen mit Hilfsmitteln wie z.B. Harz abgedichtet. Solche Dichtungen hat man allerdings in neolithischen Tongefäßen noch nicht gefunden.

5. Tongefäß aus einer Küche der Ausgrabung Kösk Hüyük ca. 5000 v. Chr. entsprechen den „Weintöpfen“ von Hajji Firuz, Iran. Arch. Mus. Nigde, Türkei.

6. Rekonstruktion einer Küche aus der Ausgrabung von Kösk Höyük , ca. 5000 v. Chr. Arch. Mus. Nigde, Türkei.

– Für die Herstellung und Nutzung von Wein in der Vorgeschichte bedurfte es einer Elite

Die bäuerliche Gesellschaft muss über eine Subsistenzwirtschaft hinausgewachsen sein um zusätzliche, nicht unbedingt lebensnotwendige Produkte zu produzieren. Im Gegensatz zu normalen landwirtschaftlichen Produkten erbringen angebaute Trauben eine geringe Ernte, sie haben eine nur sehr kurze Erntezeit und müssen sehr sorgfältig verarbeitet bzw. gelagert werden. 104 Zudem braucht man für diese „teure“ Produktion auch Abnehmer, damit sich der erhöhte Aufwand im Vergleich zu einfachen gewinnbringenden Produkten aus der Landwirtschaft lohnt. Diese Voraussetzungen waren im Neolithikum noch nicht gegeben. Alle schriftlichen und bildlichen Hinweise über die Nutzung von Wein von der zweiten Hälfte des 4.Jahrtausends v. Chr. bis etwa 1000 v. Chr. weisen ausnahmslos auf die Nutzung durch eine Elite, Priesterin und Priester, König und Königin, oder ihre höchsten Vertreter hin. Wein wurde in dieser Zeit ausnahmslos für Kulthandlungen verwendet.

Argumente die für die Existenz von Wein im Neolithikum verwendet werden

Weinsäure

Patrick E. McGovern ist Leiter des Labors für Biomolukulare Archäologie des Penn Museums, The University of Pennsylvanian Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Eine große Anzahl der relevanten chemischen Untersuchungen wurde in seinem Labor durchgeführt. In früheren Publikationen erklärt er noch, dass der Nachweis von Weinsäure sowohl Traubensaft, Traubensirup, Rosinen, Wein aber auch Produkte von anderen Früchten bedeuten kann. 105 In späteren Publikationen über Wein im Neolithikum stellt er Wein und eine Weinkultur in den Vordergrund, ohne wirklich auf das Umfeld und mögliche Alternativen einzugehen. Für Ihn ist Weinsäure ein „fingerprint“ und „biomarker“ für Wein. Ein wichtiger Ausgangspunkt waren die Befunde der Ausgrabungen in Georgien. Hier wurden von georgischen Wissenschaftlern verschiedene Indizien für die Existenz von Wein beschrieben. 106,107, 108

Traubenkerne

In einem Artikel über die Weintraubenkultur in Georgien, basierend auf paleobotanischen Daten, sind alle bisher (bis 2010) bei archäologischen Ausgrabungen in Georgien gefundene Traubenkerne aufgelistet und beurteilt. Die inzwischen etwas mehr als 10 Traubenkerne werden als kultivierte Form bezeichnet. 109

Die extrem kleine Anzahl von Traubenkernen die in den neolithischen Siedlungen um Shulaveri gefunden wurden, macht aber nach Meinung anderer Wissenschaftler eine definitive Zuordnung unmöglich. Siehe hierzu stellvertretend für viele andere: McGovern, P.E. 1997 110, und Zohary, D. 2003 111, Tengberg, M. 2012 112 und Renfrew, J.M. 2003. 113

Naomi Miller sagt ganz klar, dass zwischen dem wilden und dem kultivierte Status von Traubenkernen aus archäologischen Grabungen der Vorgeschichte nicht unterschieden werden kann. Besonders große Kerne werden gerne als Kerne von domestizierten Trauben bezeichnet, doch können ebenso gut kleine unterentwickelte Traubenkerne als Hinweis für eine Domestikation angesehen werden. 114

Traubenpollen

In einer weiteren Arbeit erklären georgische Wissenschaftler mit Pollenanalysen und chemischen Analysen das Vorhandensein von Wein im Neolithikum. Die in den Ausgrabungen neolithischer Siedlungen Georgiens gefundenen Pollen von kultivierten Trauben werden mit Pollen aus modernen Weingärten in Ostgeorgien verglichen und beides als direkten und indirekten Hinweis auf die Existenz eines Traubenanbaus gesehen. Daraus wird die Existenz von Wein im Neolithikum abgeleitet. 115 Traubenpollen der wilden und der domestizierten Form sind jedoch nicht voneinander zu unterscheiden. 116

Ähnlich kompliziert, wie die Bestimmung von Traubenkernen aus dem Neolithikum, ist auch die von Traubenpollen aus dieser Zeit.

Ein Vergleich von Pollen, die eine typische Flora aus modernen ostgeorgischen Weingärten repräsentieren 117 mit den Pollen von „kultivierten“ Trauben, die in dem neolithischen (Honig) Topf gefunden wurden, ist irreführend. Die meisten alten Darstellungen kultivierter Trauben zeigen sie hoch hängend, oder als Lianengewächse an Bäumen hoch wachsend.

Während im heutigen Ostgeorgien, aus dem die zum Vergleich verwendeten Pollen stammen, eine moderne Traubenmonokultur vorhanden ist, gibt es in Westgeorgien immer noch kultivierte, an Bäumen wachsende Traubensorten in traditioneller Form. Aber auch mit Pollen aus diesen traditionellen westgeorgischen Fruchtgärten macht ein Vergleich wenig Sinn. Bienen sind Opportunisten und keine Systematiker. Sie konzentrieren ihr Sammeln von Honig und Pollen auf Blütenpflanzen, die gerade eine große Ausbeute ermöglichen. Sie sammeln auch nicht flächendeckend und können deshalb auch nicht eine repräsentative Pollensammlung eines bestimmten Biotops zusammentragen.

Der neolithische Tontopf mit Traubendekor

Bei den Ausgrabungen in Georgien wurden Keramikscherben mit „Knubbendekor“ gefunden, Töpfe mit einzelnen, oder in Reihen geformten „Knubben“.118

Das sogenannte Traubendekor auf einem Tontopf ist wunderschön, hinzu kommt, dass in ihm Weinsäure gefunden wurde. Diese frühe neolithische Keramik ist zwar zum Kochen geeignet, man könnte darin auch Most fermentieren, doch lässt sich in solchen Tontöpfen Wein nicht über eine längere Zeit aufbewahren. Diese Töpfe sind nicht dicht und sie lassen sich auch nicht verschließen.

Einige vergleichbare Traubendekors auf Keramikscherben wurden von McGovern inzwischen in Südostanatolien gefunden. 119 Das verdeutlicht aber auch nur die schon bekannte Verbindung der Keramik aus Ostanatolien mit der aus dem neolithischen Südkaukasus.

Eine neolithische Weinkultur

In seinem Buch „Unkorking the Past“ schrieb McGovern 2009, dass die eigenen Forschungen, eine Kombination von archäologischen und chemischen Untersuchungen, es immer deutlicher machen, dass die erste Weinkultur der Welt, in der sowohl Traubenanbau als auch die Herstellung von Wein die Wirtschaft, die Religion und die Gesellschaft begann zu dominieren, mindestens um 7000 v.Chr. in den Gebirgszonen des östlichen Taurus, des südlichen Kaukasus und des nördlichen Zagros entstand. 120

Damit kann er jedoch nur die Ausgrabungen die der Shulaveri-Shomu- Tepe -Kultur im heutigen Georgien, Hajji Firuz -Tepe im nördlichen iranischen Zagros und Nevali Cori, sowie Körtig Tepe im Südosten gemeint haben. .

2003 beschrieb McGovern noch Georgien als Ursprungsland für Wein und Weinbau. 121

2004 war es der Südosten der Türkei, den er als mögliches „Homeland“ bezeichnete. 122

Inzwischen hatte man Traubenreste in Nevali Cori aus der Zeit von 8600 – 8500 v.Chr. und auch Weinsäure (tartaric acid) in einem Steintopf des vorkeramischen Körtik Tepe 9600 v.Chr. gefunden. 123

Auch bei diesen 2500 bis 3000 Jahren älteren Funden denken einige Wissenschaftler sofort und ausschließlich an Wein. Deshalb sollte man sich nicht über eine wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung mit dem Titel: „The Archaeological and Chemical Hunt for the Origins of Viticulture“ wundern. 124

Wenn nicht Wein was denn dann?

Wie schon vorher gesagt kann Weinsäure (tataric acit) nicht von Wein sondern auch von einer Reihe anderer Produkte wie Rosinen,Traubenessig, Traubendicksaft, und auch von anderen Früchten und Kräutern stammen.

Rosinen

Für die Menschen im Neolithikum sind lagerfähige Nahrungsmittel besonders wichtig. Für viele Naturprodukte gibt es nur eine kurze Saison, in der sie gesammelt oder auch angebaut und geerntet werden können. Falls man sie nicht frisch verspeist, müssen sie konserviert werden.Der einfachste Weg ein Naturprodukt haltbar zu machen, ist es zu trocknen. Es ist die älteste Verarbeitungsmethode. Trauben trocknen zu Rosinen und sind, wenn sie auch trocken und sicher gelagert werden, jahrelang haltbar. Rosinen werden in Tontöpfen allerdings nur geringe Mengen von Weinsäure hinterlassen. Möglicherweise wurden sie auch wegen der Gefahr des Schimmels in leicht durchlüfteten Behältern (Körben) und nicht in Tongefäßen aufbewahrt.

Traubenessig

Traubenessig kann nur entstehen wenn der Traubensaft vorher fermentiert hat und der so entstandene „Wein“ nicht haltbar ist. Da man mit einiger Sicherheit Fruchtfleisch und Traubenschalen mit verwendet hat, erhielt man einen sauren, Essig ähnlichen Brei. Diesen konnte man je nach Qualität des neolithischen Topfes für eine kurze Zeit verwenden. Er wird auch verdünnt nicht viel anders als fermentierter Saft von wilden Trauben geschmeckt haben. Ein solcher Essigbrei hinterlässt natürlich Weinsäure in den Poren des groben Tontopfes.

Sehr viel später haben ganze Armeen von Soldaten verdünnten Essig gerne zum Durstlöschen getrunken. Übrigens kann man in Essig sehr gut Gemüse und Früchte konservieren. Die Bauernmärkte des Nahen Ostens stehen voll mit in Salz oder Essig eingelegtem Gemüse und Früchten.

Pekmez, Traubensirup, die sinnvolle Alternative

Das Feuer wird in neolithischen Küchen, wenn auch nur auf kleiner Flamme, tagsüber immer gebrannt haben. Neben allen anderen Kochaktivitäten konnte man Fruchtsaft leicht eindicken. Es entsteht dabei ein Sirup, den man in Georgien Bakmasi, in der Türkei Pekmez nennt. Die neolithischen Feuerstellen sind meist mit festen abgerundeten Flusssteinen ausgelegt. Das Feuer brennt in der Mitte und lässt Platz um mehrere Töpfe mit ihrem Inhalt nicht nur auf, sondern auch um das Feuer herum zu erhitzen. Die erhitzten Steine halten die Wärme sehr lange. So wird Saft, auch ohne zusätzliches Holz schnell erwärmt und mehr oder weniger schnell eingedickt. Schon ab 40°C sterben die meisten Hefen ab, der Saft kann nicht mehr fermentieren. Pekmez ist auch noch in schlechten Tongefässen haltbar, es verschließt grobe und leckende Töpfe. Diese kann man dann abdecken, braucht sie aber nicht abzudichten.

Pekmez, allein oder zusammen mit Mehl, Hülsenfrüchte oder anderen Nahrungsmittel ist extrem nahrhaft und süß. Mit diesen Eigenschaften ist Pekmez das ganze Jahr über der Renner für Vorspeise, Hauptgang und Nachtisch.

Die Domestizierung von Trauben ist kein zwingender Beweis für Wein.

Ich halte es für durchaus denkbar, dass im Neolithikum Trauben anfangs zur Sicherung hochwertiger Nahrungsmittel und vorrangig für mehr und besseres Pekmez domestiziert wurden und nicht für Wein. 125

Wollte man Wein produzieren, so mussten nicht nur Anbauflächen aus der Nahrungsmittelproduktion herausgenommen werden, es mussten auch Käufer, bzw. Nutzer vorhanden sein, die sich Wein leisten konnten. Diese „Elite“ kennen wir aber erst aus der frühen geschichtlichen Zeit. Traubensirup wird in frühen historischen Dokumenten oft genannt. Jedoch wurden bei vielen Übersetzungen diese Produkte falsch bezeichnet oder beschrieben, weil die meisten Autoren sie nicht kennen. Traubensirup hinterlässt in jedem Tontopf Weinsäure.

7. Produkte aus Fruchtdicksaft / georgisch Bardagi/ türkisch Pekmez.

Noch mal Hajji Firuz Tepe

Bei den Ausgrabungen von Hajji Firuz Tepe wurden in einer Küche 6 Tontöpfe mit einem Fassungsvermögen von je etwa 9 Litern gefunden. In 2 der Töpfe fand man Rückstände die auf die Verwendung von Trauben hinwiesen. Die Töpfe sind zwar für die Herstellung, aber nicht für die Aufbewahrung von Wein geeignet und lassen sich auch nicht luftdicht verschließen. Für die Menschen stand um 5400 v. Chr. immer noch die Sicherung zusätzlicher und lagerfähige Nahrungsmittel im Vordergrund.

Sehr viel wahrscheinlicher ist hier in der Küche einer kleinen neolithischen Siedlung statt Wein Pekmez, d.h. eingedickter Traubensaft, hergestellt wurde. Er schließt grobporige Gefäße, bleibt über sehr lange Zeit haltbar und muss nicht verschlossen aufbewahrt werden. Zudem nimmt Pekmez in der Subsistenzwirtschaft einen sehr wichtigen Platz als Nahrungsmittel ein. Möglicherweise war der Traubendicksaft noch mit einem anderen Produkt vermischt, vielleicht mit Mehl, oder auch mit anderen Früchten sowie mit dem Harz des Terebinth-Baums zur Verbesserung des Geschmacks. Das könnte auch eine Erklärung für die unterschiedliche Färbung in den gefundenen Rückständen sein.

In einem der beiden Töpfe erkannte man einen rötlichen Rückstand und in dem zweiten Topf einen gelblichen Rückstand. 126 In beiden Töpfen fand man Weinstein, in einem der Töpfe noch Weinsäure. 127, 128

Da die Beeren von wilden Trauben rot sind, müsste man bei weißen Trauben davon ausgehen, dass die Trauben schon kultiviert und weiße Trauben das Resultat einer langen Auswahl sind. In Anbetracht der allgemein vorliegenden archäologischen Befunde ist dies in der Zeit um 5400 v.Chr. noch unwahrscheinlich.

Terebinth

Das Harz des Terebinth Baums, einer Pistazienart, ist für eine Geschmacksverbesserung besonders geeignet. Plinius der Ältere hat in seiner Naturgeschichte ausführlich über diese Verwendung von Terebinth und anderen Harze berichtet. 129

Der Terebinth Baum ist mit zwei Arten im Mittelmeerraum und darüber hinaus weit verbreitet. Im Vorderen Orient, besonders entlang der Küste des östlichen Mittelmeers werden seine Blätter zur Aromatisierung von Gemüse, besonders zusammen mit Hülsenfrüchten gekocht, die Blüten in das Dorfbrot eingebacken, die Früchte getrocknet und gemahlen. Daraus macht man dann einen „Kaffee“ (türkisch = citlik kahve`si). Das Harz ist ein konzentriertes Aromat.

In seinem Artikel über den frühesten Fund eines alkoholischen Getränks aus China erwähnt P. McGovern auch andere „Wein“ -Funde aus der Zeit der Shang und Zhou Dynastien (ca. 1200 v. Chr.) und beschreibt kleine Bronzegefäße mit „Wein“ aus Reis und Hirse, gewürzt mit Kräutern, Blüten und Harzen. 130

In einer bronzezeitlichen Schiffsladung voll mit Amphoren war ein beträchtlicher Teil der Gefäße (ca. 1000 kg) mit Terebinth Harz gefüllt. Es sollte der Aromatisierung von Speisen und Getränken in Ägypten dienen und nicht, wie vielleicht zuerst vermutet, für die Haltbarmachung von Wein genutzt werden. Das Schiff sank vor der türkischen Küste. 131

Auch für den medizinischen Bereich wurde das Harz benutzt. Man schreibt Terebinth schützende Eigenschaften gegenüber bestimmten Bakterien zu. Wie unsere Versuche gezeigt haben, kann Terebinth aber nicht den Wein davor schützen, zu Essig zu werden. Es sei denn man verwendet das Terebinth Harz zum Verschließen von Amphoren (wobei es natürlich auch sein Aroma abgibt) und trägt damit zur besseren Haltbarkeit ihres Inhalts bei .Auch wurde der berühmte griechische Retsina nicht mit Harz versetzt, um ihn haltbar zu machen, sondern um ihn den Geschmack zu geben, den die Griechen so an ihm lieben.

Kultivierte Trauben und ihre Verbreitung

Margareta Tengberg, Archäobotanikerin an der Universität Paris 1 arbeitet mit ihren Studenten in verschiedenen Ausgrabungen des Vorderen Orients. In ihrer rezenten Publikation „ Fruit Growing“ beschreibt und begründet sie die ersten Anzeichen der Kultivierung von Trauben, Oliven, Feigen und Datteln im Chalkolithikum. 132

Es ist genau die Zeit, in der bei vielen Ausgrabungen immer größere Mengen von Traubenkernen gefunden werden, die eine sichere Unterscheidung zwischen Kernen wilder und kultivierter Trauben zulassen. Auch die Funde verschiedener typischer Anlagen, Geräte und Gefäße weisen auf eine zunehmende wirtschaftliche Nutzung der Trauben und andere kultivierte Früchte hin. In vielen Fällen bleibt jedoch noch immer die Frage offen in welcher Form Trauben genutzt wurden. Interessant ist jedenfalls, dass neben den kultivierten Trauben auch weiterhin bedeutende Mengen wilder Trauben verwendet werden. Detaillierte Informationen stammen aus einer Reihe von Grabungen in Griechenland etwa ab 4500 v. Chr. N.F. Miller argumentiert: „Überzeugende Belege für die Nutzung von domestizierten Trauben, sind aus dem vierten Jahrtausend bekannt und die weite Verbreitung der domestizierten Trauben in Gebiete außerhalb ihres natürlichen Vorkommens geschah nicht vor dem dritten Jahrtausend v. Chr.“ 133

Die Zeit der Küps, Karas, Kvevris, Dolias, Pithos, Tinajas, Talhas de barro und Amphoren, der Gefäße für die Produktion, die Aufbewahrung und den Transport von Nahrungsmitteln und von speziellen Handelsgütern wie zum Beispiel Öl und Wein.

In diese Periode gehört die Ausgrabung der Areni I. Höhle. Nach Aussagen von G. Areshian, dem Co-Direktor der Ausgrabung, fand man hier die erste komplette Produktionsanlage für Wein. Er begründete dies u.a. damit, dass es in dieser Zeit keine Möglichkeit gab, Saft ohne Fermentierung zu konservieren und jeder fermentierte Saft sofort sauer wird. Deshalb so folgerte er, muss der Inhalt mit großer Sicherheit Wein gewesen sein! Es ist schon seltsam, dass ihm die Haltbarmachung von Traubensaft durch Erhitzen nicht einfällt, obwohl er in Armenien umgeben ist von Produkten mit und aus Traubendicksaft.

H. Barnard wendete für die Untersuchungen von den in Areni gefundenen Rückständen aus dem Bereich der Kelterei eine neue Methode erfolgreich an. Was ebenso wichtig ist, er diskutiert erstmals kritisch die bisherigen Methoden von chemischen Untersuchungen und ihre Interpretationen. Nach Barnard können sie nicht als sichere Indikatoren für die Existenz von Wein verwendet werden. 134

Bisher wurden bestimmte chemische Verbindungen in Rückständen von alten Keramiken oder anderen Behältern als Indikatoren für Wein angesehen und verwendet. Zu diesen Verbindungen gehört Weinsäure (tartaric acid), aber auch Harz (Terebinth), das absichtlich dem Wein zur Haltbarmachung oder zur Geschmacksverbesserung hinzugefügt wurde. 135

Das Vorhandensein von Weinsäure belegt aber nicht schlüssig die vorherige Existenz von Wein, da Weinsäure auch in vielen anderen Gemüse und Früchten vorkommen. So hat zum Beispiel Weißdorn, er kommt sowohl im gesamten Ostanatolien, wie auch im Kaukasus reichlich vor, eine viel höhere Konzentration von Weinsäure als Trauben. Barnard argumentiert weiter, dass Weinsäure sehr leicht in Wasser löslich ist und schnell aus vergrabenen Töpfen austreten oder auch eintreten kann und somit das Vorhandensein oder das Nichtvorhandensein von Weinsäure nur schwer zu interpretieren ist.

Deshalb kann Weinsäure nur als ein verlässlicher Indikator für alle Produkte von Nahrungspflanzen gelten, in denen sie vorkommt. Aber auch Weinsäure von Trauben muss nicht unbedingt Wein belegen, sondern kann Traubensaft, Rosinen und konzentrierter Traubensirup wie z.B. das aus Klassischer Zeit bekannte „defrutum“ oder das moderne „pekmez“ oder auch Essig anzeigen.

Harz, das bei Ausgrabungen gefunden wird, kann mit einer Anzahl von Nutzungen in Zusammenhang gebracht werden. Hierzu gehört das Dichten von unglasierten Gefäßen. Es kann auch verwendet werden, um Wein bei der Verarbeitung zu schützen oder den Geschmack zu verbessern. 136

Anfangs wurde Wein wahrscheinlich weder lange gehalten, noch weit transportiert. Und so folgert Barnard, dass Spuren von Harz in Funden aus dem Neolithikum in sich selbst kein Beweis für das frühere Vorhandensein von geharztem Wein sein kann.

Barnard beschreibt dann Malvidin als einen besseren chemischen Indikator für Rotwein. Malvidin gibt Trauben und ihrem Wein die rote Farbe. Nur wenige andere Pflanzen, dazu gehört allerdings auch der Granatapfel, haben Malvidin. Andere malvidinhaltige Pflanzen sind Blaubeeren (Vaccinium myrtillus), Rotklee (Trifolium pratense) und Malve (Malva sylvestris).

Zusammenfassend schreibt Barnard, dass Malvidin auf zwei Keramikscherben aus der Areni Höhle, datiert auf das späte Chalkolithikum etwa um 4000 v. Chr. zwar nicht direkt Rotwein, sondern Reste von roten Trauben oder vom Granatapfel, oder von beiden Früchten belegt. Eine Fermentation kann nur vermutet und andere Produkte wie „defrutum“ sollten nicht ausgeschlossen werden. Im Zusammenhang mit den archäologischen Funden, so Barnard, ist unser chemisches Resultat als ein zusätzliches Argument für oder gegen das Vorhandensein von Wein in bestimmten Tongefässen zu sehen. 137

Da die Bearbeitungsmethode von Trauben für Wein und für Pekmez die gleiche ist, halte ich es für möglich, dass die Areni I. Anlage sowohl für die Produktion von Wein als auch von Pekmez oder für beides verwendet werden konnte.

Wein für die Elite

Schauen wir in die frühgeschichtliche Zeit, so weisen alle schriftlichen und auch die bildlichen Zeugnisse über die Nutzung des Weins ausnahmslos auf den Genuss durch eine Elite, durch Priesterinnen und Priester, Könige und Königinnen, oder ihre höchsten Beamten hin. Dies betrifft den Zeitraum von der zweiten Hälfte des 4. Jahrtausends bis etwa 1000 v. Chr. Das passt zu den archäologischen Funden aus dem späten Chalkolithicum und der Bronzezeit. In Dörfern fand man keine Gefäße oder andere explizit auf Wein hinweisende Funde. Die ersten größeren Weingefäße stammen aus den Depots von Tempeln, herrschaftlichen Häusern und aus Pharaonen- und Fürstengräbern. Neben Kultgefäßen fand man hier aus Ton gebrannte Vorratsbehälter unterschiedlicher Größe in denen Getreide, Öl, Früchtesirup, Wein und andere Flüssigkeiten aber auch Trockenfrüchte, Fleisch und andere Produkte aufbewahrt wurden.

Ein früher Hinweis für Wein in Tongefäßen kommt aus Abydos in Ägypten. Obwohl zu dieser Zeit noch keine Trauben in Ägypten angebaut wurden, fand man bei der Ausgrabung des Grabes von König Scorpion I. ca. 700 Amphoren mit einem geschätzten Inhalt von 4500 Liter Wein. Die Funde wurden auf 3150 v. Chr. datiert. Hierbei fand man auch die frühesten Hieroglyphen aus Ägypten. Sie bezeichnen Inhalt und Herkunft der Produkte. Das ägyptische Wort für Wein war „ irp „. Die in einigen der Amphoren gefundenen Rückstände belegen, dass der Wein mit Harz, Quendel (Satureja), Melisse, Senna (Cassia), Koriander, Gamander (Teucrium), Minze (mentha), Salbei (salvia) bzw Thymian (thymus) gewürzt war. Der Wein und die verwendeten Amphoren stammten aus der südlichen Levante. 138

Später, aus Zeit des Pharao Tutmosis, kennt man Listen mit Produkten, die in Amphoren transportiert wurden. Dazu gehörten Olivenöl, Honig, Wein, Milch, Fleisch, Geflügel, Fisch, Käse, Getreide, Bohnen, Kohl, Früchte, Kräuter, Nüsse, Zucker (Sirup ?) und Harz. (Quelle: Museum für Unterwasser Archäologie, Bodrum, Türkei)

Ein besonders interessanter Fund ist das bisher älteste gefundene Schiffswrack im Mitteleerraum, das bei Uluburun, an der anatolische Südküste gefunden wurde. Das noch weitgehend intakte Schiff war ein 20 Tonnen Handelsschiff aus dem 14. Jahrhundert v. Chr., das Waren aus dem gesamten Mittelmeerraum und Teilen Mitteleuropas mit sich führte. Es gab Elfenbein, Gold, afrikanisches Hartholz, Fayancen, zehn Tonnen Kupfer aus Zypern und andere wertvolle Gegenstände. Andere Produkte, wie z.B. über 1000 kg Terebinth Harz für die Parfum Herstellung waren in kanaanitischen Amphoren, Glasperlen und Eicheln, Mandeln, Feigen, Oliven und Granatäpfel waren in anderen Amphoren unterschiedlicher Herkunft verpackt. Ein Teil der über 150 Amphoren und Dolias mit einem Fassungsvermögen von bis zu 400 Liter waren leer. Vielleicht sollten diese mit anatolischem Wein gefüllt werden? 139

Ein gutes Beispiel für die unterschiedlichen Verwendungen kann man an den Küps (Tongefäß aus Anatolien) sehen, die noch heute im früheren Depot des Haupttempels der hethitischen Unterstadt von Hattuscha stehen.

8. 4 große Küps im früheren Depot des Tempels der Unterstadt von Hattuscha ca. 1350 v. Chr. Türkei

Die ersten beiden Küps, sie fassen etwa 400 Liter, haben am Rand der Öffnung eine breite Lippe (Rand). Die beiden anderen Küps dahinter – einen dünnen und abgerundeten Rand. Die ersten beiden Küps kann man dicht verschließen. Möglicherweise wurde in ihnen Wein aufbewahrt. Die beiden anderen Küps enthielten vielleicht Mehl oder Getreide, man hat sie wahrscheinlich nur abgedeckt. Diese Küps stammen aus der Zeit um 1350 v. Chr. Das in der Türkei verwendete Wort „Küp“ für ein großes Tongefäß ist kein türkisches Wort. Wahrscheinlich ist es mit dem deutschen „Kübel“ und dem englischen „cup“ verwandt und deshalb wohl Indo-Europäisch.

Mit der weiteren Entwicklung der Schrift, sowohl der Keilschrift in Mesopotamien als auch der Hieroglyphenschrift in Ägypten und in Anatolien erfahren wir mehr über große und kleine Gefäße und über typische Wein- und kultischen Trinkgefäße. Mit dem in der Bronzezeit schnell expandierenden Handel und den immer komplexeren Kulthandlungen zur Festigung weltlicher Macht ging ihre schnelle Verbreitung einher.

9. Große, ca. 300 Liter Amphore aus dem Schiffswrack von Uluburun. ca. 1400 v. Chr. Unterwasser Mus. Bodrum, Türkei.

10. Amphore aus Kanaan, Schiffswrack von Uluburun, ca. 1400 v. Chr. Unterwasser Mus. Bodrum, Türkei.

11. Amphoren aus Zypern, Schiffswrack von Uluburun, ca. 1400 v. Chr. Unterwasser Mus. Bodrum, Türkei.

12. Amphoren von Chios, Schiffswrack von Uluburun, ca. 1400 v. Chr. Unterwasser Mus. Bodrum, Türkei.

Hethitische Tongefäße

Viele Hinweise auf kultivierte Trauben, zusammen mit Funden von Weinsäure in Steinkeltern (z.B. Titriş Höyük) stammen aus der frühen Bronzezeit (ab 3200 v. Chr.) und belegen, dass zu dieser Zeit der Traubenanbau, zusammen mit dem Anbau anderer Früchte, eine schon weiter verbreiterte Wirtschaft in den östlichen und südlichen Gebieten Anatoliens war.

Entsprechend entstanden in dieser Zeit auch eine Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Gefäße für die Lagerung, den Transport und die Nutzung von verschiedenen Nahrungsmitteln, u.a auch für Wein.

In hettitischen Texten sind Tongefäße aller Grössen genannt wie “ huppar, harsi, huptushi, hanissa“. Sie wurden aber nicht nur für Wein sondern auch für Öl, Bier und andere Nahrungsmittel verwendet. Leider geben die frühen Daten keine Hinweise über die genaue Größe und Verwendung. 140

Das große Tonfass, hettitisch“ luli” ,wurde wahrscheinlich auch als Kelter zum Treten der Trauben verwendet. 141

Die aus Ton hergestellten Badewannen aus der Ausgrabung Kültepe, datiert auf ca. 1900 v.Chr. wurden von dem Archäologen T. Özgüc wegen ihrer Fundnähe zum Ofen und meist in einer Ecke des Raumes stehend als Gefäß für die Weinproduktion genannt. 142 Doch haben die meisten dieser großen „Wannen“ eine eingebaute Sitzbank und sind deshalb dann doch Badewannen.

13. Hethitische Badewanne aus Ton, kein Weingefäß, aus Kültepe ca. 1700 v. Chr. Arch. Mus. Kayseri, Türkei.

14. Großes Kultgefäß mit Stierkopf aus der Ausgrabung Kültepe ca. 1800 v. Chr. Arch. Mus. Kayseri, Türkei.

Nach Müller Karpe, der an den Ausgrabungen der hettitischen Hauptstadt teilnahm, waren „harsi“ und „harsialli“ große Gefäße aus den Tempeldepots. Sie konnten zwischen 900 bis 1750 Liter fassen.143

Die kleineren Tonfässer hießen „harsiyallani“, sie hatten einen besonders breiten Rand, wodurch die Fässer gut verschlossen werden konnten. Eine jeweils grosse Zahl dieser Tonfässer aus der Zeit um 1700 v.Chr. wurde in den Ausgrabungen von Kültepe, Alisar, Masat sowie Acem Höyük gefunden. 144

In Hattuscha waren kleine Weingefäße mit langem Hals besonders zahlreich. Sie heißen „hanelissa“ , fassen ca, 1,5 -2 Liter und wurden für die Lagerung und den Transport von Wein verwendet. 145

15. Ausgrabung Acem Höyük, U.H. mit einem Randstück eines ca 4000 Liter fassende Küps, auf dem Boden die Reste des Küps, um 1600 v. Chr., Türkei.

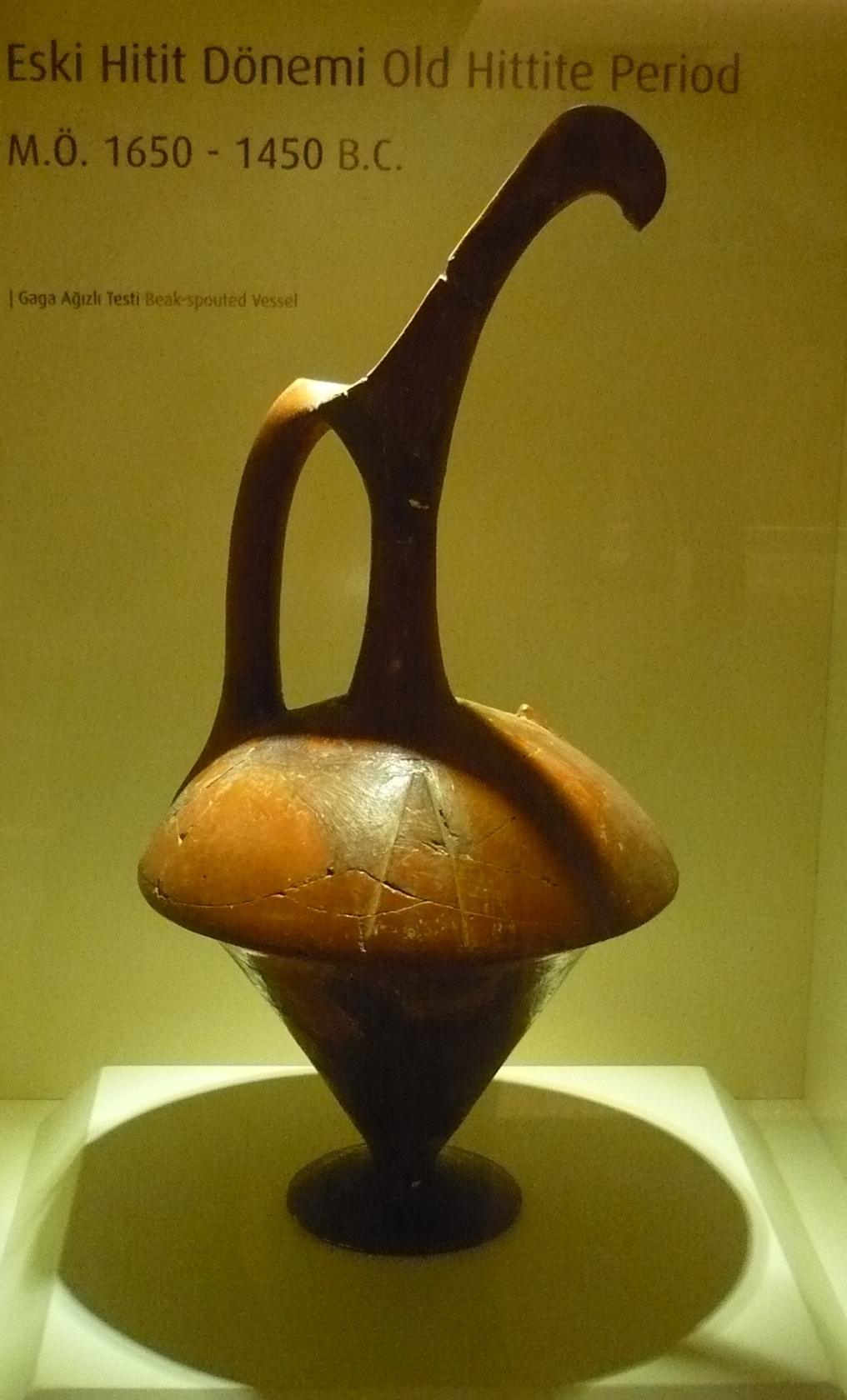

Trinkgefäße

Schnabelförmige Trinkkannen sind oft in der hettitischen Ikonographie dargestellt, Ihr Name ist „ispantuzzi“ d.h. Trinkopfer-Gefäss (Müller Karpe 1988:25). Solche Weinkannen sind von der altassyrischen Kolonie- Periode bis zum Ende des Hettitischen Großreichs um 1200 v. Chr. bekannt. 146 Zu den besonderen Gefäßen gehört auch ein ca. 600 Liter Gefäß aus der Ausgrabung Kültepe, dessen oberer Teil in einen Stierkopf als Ausguß endet.

16. Schnabelvase aus Hattuscha ca. 1650 – 1450 v. Chr. Arch. Mus. Bogazköy, Türkei

17. Frühe hethitische Weingefäße um 1500 v. Chr. Arch. Mus. Bogazköy, Türkei.

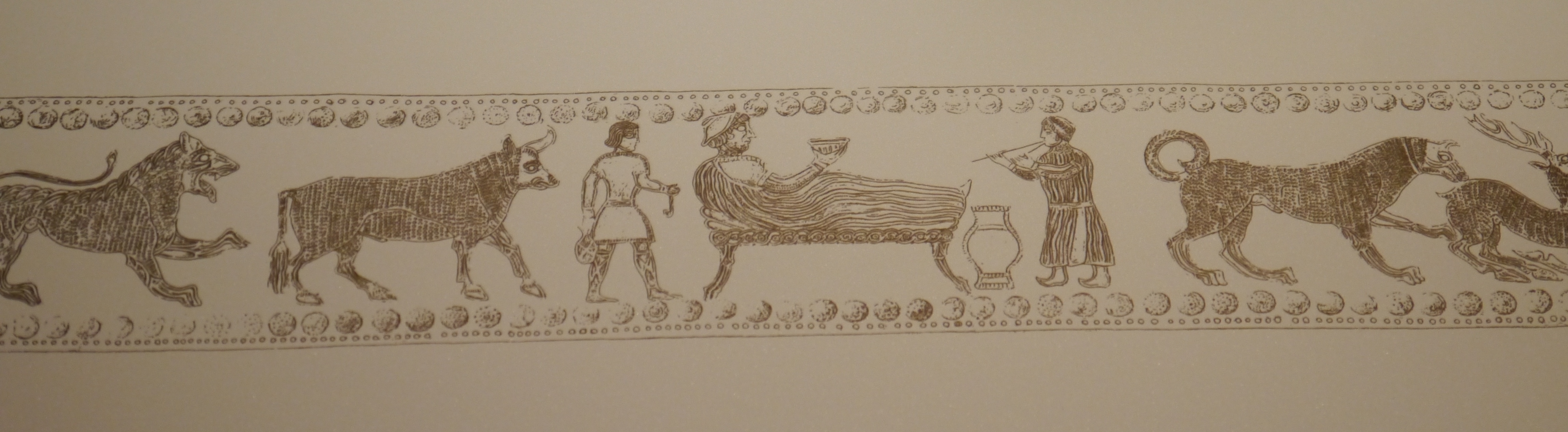

Die große berühmte Reliefvase aus der Ausgrabung von Inandik Tepe (1600-1400 v.Chr.), zeigt einen Teil der Weinproduktion und verschiedene Trink- und Transportgefäße. Im ältesten Hethiter Tempel, ebenfalls in Inandik, fand man eine Anzahl von sehr großen Tonfässern, die nicht nur der Lagerung dienten, sondern wahrscheinlich auch für die Produktion von Wein genutzt wurden.

Zu den ausgefallenen Trinkgefäßen gehört auch der Trinkopfer-Arm, hettitisch „kattakurant“. Viele von ihnen wurden in den Tempeln der Oberstadt von Hattusha gefunden und gelten als besonders wichtige Kultgeräte. Weiterhin waren Trinkgefäße in Form von Tierköpfen, in hethitisch „bibru“ zwischen 2000 v.Chr. und dem Zusammenbruch des hettitischen Reichs um 1200 v.Chr. in Mode. 147

Doch das am meisten abgebildete Trinkgefäß ist eine kleine dünne Trinkschale. Sie heißt „huppar“. Meist wurde sie für Trinkopfer verwendet, sie galt aber auch als ein bedeutendes Symbol für eine erfolgreiche königliche Reichsführung.

18. Das Festmahl des Asurbanipal und seiner Gattin mit Opferschale, (669-631 v. Chr.) Assyrien. Gezeichnet von Hacer Özkaya nach einer Vorlage von : Perrot,G & C. Chipiez: A History of Art in Chaldea & Assyria. London 1884.

19. Zeichnung eines Silbergürtels. Festmahl, Fürst mit Opferschale, ca. 3. Jahrh. v. Chr. aus Ani, Staatl. Mus. Tiflis.

Weingefäße in Mesopotamien

Süd- Mesopotamien war ein typisches Bierland. Aus der Handelsstadt Nippur sind zwar mehr als dreitausend Dokumente bekannt, doch gab es nur einige wenige Hinweise über Trauben, die fast alle mit „geštin had“, das heißt, getrocknete Traube bzw. Rosine benannt waren.

In den umgebenden Länder hingegen gab es zumindest mehr Hinweise auf Trauben, denn in den meisten Ausgrabungen aus dem 4. Jahrtausend v. Chr. fand man schon regelmäßig Traubenkerne. In Palast von Mari standen im Lagerraum No. 116 viele große Tonfässer ca. 1,5 Meter hoch, der Durchmesser der Öffnung betrug 50 cm, der Umfang des Fasses betrug 128 cm. Die Fässer standen in einem Sockel und wurden für Öl benutzt. Doch wie man aus einem Brief des Zimri-lim an seine Frau Sophtu entnehmen kann, gab es auch Wein. Er schrieb „ fülle die Fässer mit rotem Wein und versiegle sie mit diesem Siegel…“ 148

Mit dem Begriff „Pithos“ wurden ursprünglich nur große Tongefäße aus minoischen Palästen auf Knossos für die Lagerung verschiedener Produkte bezeichnet. Ihre Kapazität ging von 50 -1500 Liter. Später wurde dieser Begriff allgemein für Lager- und Transportgefässe der verschiedenen Mittelmeerkulturen verwendet.

20. Phytos ca. 3. Jahrh. v. Chr. Staatl. Mus. Tiflis, Georgien

Das sie auch für Wein verwendet wurden, zeigte sich bei Ausgrabungen von Myrtos auf Kreta. In Raum 80 wurde ein Pithos mit gepressten Traubenschalen, Traubenkernen und Rappen, datiert auf ca. 2170 v. Chr. gefunden. 149

Dies könnte ein Hinweis auf eine mögliche Fermentierung von Traubenmaische in solchen großen Gefäßen sein. Diese Annahme könnte auch ein kleines Loch, welches oft im unteren Pithos vorhanden ist, erklären. Wird der Wein mit der kompletten Maische fermentiert, so bleiben ein großer Teil der Traubenschalen, Kerne und Rappen an der Oberfläche. Will man nun den Wein von oben entnehmen, so muss man zuerst eine beträchtlich dicke Schicht von Traubenresten durchdringen. Will man diese mühselige Arbeit umgehen, so ist es einfacher, den sauberen Wein durch ein kleines Loch im unteren Bereich des Pithos abzuzapfen.

Ab etwa 2000 v.Chr. ändert sich langsam die Form der Tongefäße. Der hauptsächlich flache Boden von großen Lager- und Transportgefäßen wird langsam rund zulaufend. Hierdurch wird der Druck den der schwere Inhalt auf die Schwachstelle zwischen dem Boden und den Seitenwänden erzeugt vermindert. Solche Pithos sind stabiler. 150

Handel und Transport von festen und flüssigen Waren.

Um etwa 2000 v. Chr. war Karkemisch (heute an der Grenze zwischen Syrien und der Türkei) das Zentrum des Weinhandels. Zu dieser Zeit transportierten Schiffe bis zu 600 Amphoren zu je 30 Liter und in großen Pithoi zu je 600 Liter Wein. In der akkadischen Sprache hießen die großen Gefässe „naspakum“. In Babylon wurden „naspakum“ bis zu einem Fassungsvermögen von 3000 Liter verwendet.151

Kurze Zeit später, etwa um 1700 v. Chr. gibt es erste Hinweise auf die Verwendung von Tierhäuten für den Transport von Wein aus Syrien. Sie werden zu dieser Zeit „ ziqqu“ genannt. Viel später erfährt man aus der berühmten Beschreibung des Festes zur Einweihung des neuen Palastes von Ashurnasirpal in Kalah (ca. 880 v. Chr.), dass 10 000 Tierhäute mit Wein (Weinschläuche) den Gästen zur Verfügung standen.152 Die älteste bildliche Darstellung für die Verwendung von Weinschläuchen für den Transport von Wein sind auf Shalmanesers ( 860-824 v. Chr.) Bronzetür von Balawat abgebildet. In seinen Analen wird dazu erwähnt, dass der Wein als Tribut aus dem Gebiet südlich des Van Sees und aus Unki nahe des syrischen Ortes Alalakh kam. 153

Georgische Namen für Weinfässer

Die frühesten Tongefässe Georgiens, sie stammen aus dem keramischen Neolithikum, haben die gleichen Formen, wie man sie auch aus anderen Regionen kennt. Sie entsprechen der Form eines Erdloches, in der gezeichneten Ansicht, einem U. In der Folgezeit lassen sich im Verlauf des Chalkolithikums (Eneolithikum) kaum Veränderungen in Form und Verwendung erkennen. Erst im Verlauf der Bronzezeit kann man regionale Unterschiede feststellen. Wie A. Bochotschadze schreibt gab es ab der Mitte des 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Weingefäße die der Form der heutigen georgischen Weingefäße (Kvevris) entsprechen. Unterschiede zu den Gefäßen aus dem Mittelmeerraum und Mesopotamiens erklärte er durch jeweils unabhängige Entwicklungen. Ab dem 7. Jh, v. Chr. kennt man Tongefäße die speziell für die Weinherstellung und Weinaufbewahrung bestimmt waren. Sie wurden noch nicht in die Erde eingegraben Doch waren auch solche Gefäße bis ins 3. Jh. v. Chr. noch nicht besonders groß. Sie hatten einen breiten, flachen Boden. Tongefäße aus der Kolchis (Westgeorgien) waren an Bauch und Schultern mit Ornamenten verziert. Ab dem 3.Jh. v. Chr. änderte sich die Form der Weingefäße. Der Hals wurde zylinderförmig, der Bauch größer und mit Mustern verziert. Viele Tongefäße bekamen Henkel zum Tragen. Einige dieser Gefäße wurden zu einem Teil in die Erde gesetzt. Ab dem 4.Jh. n. Chr. wurden Weingefäße, besonders die großen, ganz eingegraben.

Bis ins 3. Jh. n. Chr. wurden Tongefässe auch für die Beerdigung von Verstorbenen verwendet. Ihrem Inventar nach waren sie nicht reich ausgestattet und scheinen nur für einfache Vertreter der Gesellschaft benutzt worden zu sein. Man vermutet, dass in diesen Weinfässern Weinbauern beigesetzt wurden, denen auch diese Gefäße zu Lebzeiten gehörten.

Bis zum 11. Jh. n. Chr. sind Tongefäße für Wein einfach in die Erde eingegraben. Danach begann man diese Weingefäße mit einem Kalksteinmantel zu umgeben. Der Grund dafür war bestimmt das starke Erdbeben von 1088-1089. Aus der späteren Antike und frühfeudaler Zeit kennt man größere Kvevris wie es sie auch im heutigen Georgien gibt. 154

Die ältesten historischen Belege der georgischen Schrift wurden 1950 in einem georgischen Kloster in Bethlehem (Palästina, ca. 430 n. Chr.) und im Kloster Bolnissi Sioni (Georgien, ca. 480 n. Chr.) gefunden. Aus dieser frühen Zeit sind noch nicht Namen und Verwendung verschiedener Gefäße bekannt. Aus schriftlichen Quellen anderer Länder über Georgien tauchen Beschreibungen und Bezeichnungen im Klassischen Altertum auf.

Die neuesten Forschungen konnten zahlreiche alte Begriffe für Rebe, Rebsorten, Weinanbau, Wein, Weinaufbereitung, sowie Trink- und Weingefäße in der georgischen Sprache festlegen. Natürlich wurden Tongefäße in Georgien auch für viele andere Lebensmittel verwendet, so wie man das aus anderen Ländern kennt. Hier liste ich jedoch nur einige Namen für Weingefäße aus Ton auf:

Tschuri, Kvevri, Dergi, Lagvani , Kvibari, Kubari, Lachuti, Kotso, Lagvni, Lagvnari, Chalani, Deda Kvevri, Zedasche-Kvevri , Sababilo Churi, Tschassavali.

„Tschuri“ – ist ein alter Begriff, der in ganz Georgien bis zum 15. Jh. für alle Arten der Tongefässe verbreitet war. Er wird in Westgeorgien bis heute für große und mittelgroße Weingefäße verwendet. Laut Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani ist „Tschuri“ ein Behälter für Tkbili (tkbili = süss), so nennt man den frischen, ungegorenen Traubensaft in Georgien. 155

„Kvevri“ ist zwar aus dem 15. Jh. Bekannt, setzt sich aber als Begriff für ein Weinfass im 17.Jh. zunächst in Ostgeorgien und dann auch in ganz Georgien durch. „Tschuri“ dagegen wird nur noch in West-Georgien verwendet. 156

Nach Giorgi Barisashvili ist die Semantik des Wortes „Kve-vri“ eng verbunden mit dem georgischen Wort „kve-vit“ = unten, und deutet auf ein Gefäß das „unten“, in die Erde eingesetzt ist. 157

„Dergi“ ist ebenfalls ein alter Begriff, er wird bis heute in Meskheti benutzt (Orbeliani. Sulkhan-Saba, 1685-1716)

„Lagvani“ wird für große und mittelgroße Gefäße in Westgeorgien (Odischi) bis heute verwendet. ( Djavachischwili, Ivane 1986)

„Kvibari“ ist ein kleineres Gefäß für Wein, das in West-Georgien (Gurien und Imeretien) benutzt wird ( Djavachischwili, Ivane. 1986)

„Lachuti“ ist der Name für ein kleineres Weingefäß in West-Georgien (Mengrelien) (Djavachischwili, Ivane. 1986)

„Kotso“ nennt man ein kleines Gefäß für Wein in Georgien, besonders in Westgeorgien. (Orbeliani. Sulkhan-Saba, 1685-1716)

„Lagvnari und Chalani“ sind alte georgische Begriffe für Weingefäße unterschiedlicher Form und Nutzung.

„Deda Kvevri“ aus Ostgeorgien ist ein sogenannter Mutter-Kvevri, also ein „Haupt Kvevri“, in dem der größte Teil des Weines einer Familie aufbewahrt wurde (Barissaschwili, Georgi. 2012).

„Zedasche Kvevri“ ein spezieller Begriff, der sich allerdings auf die Verwendung des Wein bezieht. Man benutzt ihn meist im Osten, in Kacheti. Der „Zedasche Kvevri“ enthält einen Wein, der unter großer Aufmerksamkeit und Vorsicht für kultische Handlungen in der Kirche oder auch für bestimmte Festlichkeiten in den Familien hergestellt wurde. 158

„Sababilo Churi“ ist ein weiterer Begriff, der sich auf den Inhalt bezieht. Mit „babilo“ bezeichnet man in Georgien am Baum wachsende Rebsorten. „Sababilo Churi“ ist durch schriftliche Überlieferungen aus dem 12. und 13. Jh. belegt. „Sababilo“ ist also ein Churi mit Wein von Reben, die am Baum wachsen. 159

“Tschassavali” dieser Begriff ist verhältnißmäßig neu.